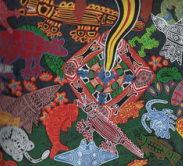

"Ah, the emotions of supernatural beings reflect the meaning of human existence!"

Jenshi chuan, T'ang folktale

Jesse, the buddhist santa cruz therapist, listens and reflects. She helps to pan for gold. All the nuggets say: time to go. Time from the administration dungeon, a profession I no longer fathom, the classroom, students I love. Time to seek integration. Why, why do I linger? She listens. At the end of our last session, she is quite still. She leans back, then forward. She says, "do not become the fox." I nod and shift on the soft couch, not quite comprehending. The room is warm and dark. I check the lithograph of birds above her head.

I imagine Kitsune no Yomeiri, the eerie fox wedding in Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurasawa's film Dreams. No, not that fox. She means the wild fox, the fox of fools. The monk who becomes a wild fox for 500 lifetimes because he mistakes the question of cause and effect. I don't know this fox, or how to follow the warning: Take Notice. I google wild fox koan and find Japanese Zen master Dōgen Zenji's wild fox koan.

Jenshi chuan, T'ang folktale

Jesse, the buddhist santa cruz therapist, listens and reflects. She helps to pan for gold. All the nuggets say: time to go. Time from the administration dungeon, a profession I no longer fathom, the classroom, students I love. Time to seek integration. Why, why do I linger? She listens. At the end of our last session, she is quite still. She leans back, then forward. She says, "do not become the fox." I nod and shift on the soft couch, not quite comprehending. The room is warm and dark. I check the lithograph of birds above her head.

I imagine Kitsune no Yomeiri, the eerie fox wedding in Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurasawa's film Dreams. No, not that fox. She means the wild fox, the fox of fools. The monk who becomes a wild fox for 500 lifetimes because he mistakes the question of cause and effect. I don't know this fox, or how to follow the warning: Take Notice. I google wild fox koan and find Japanese Zen master Dōgen Zenji's wild fox koan.

When Zen Master Daichi of Hyakujo-zan mountain in Koshu gives a dharma talk, he sees an old man is along with the monks. The old man usually vanishes when the talk is over, but one night he does not leave. Master Daichi asks who he is. The old man says "I am not a person. I have been a wild fox for five hundred lives. In the era of Kasyapa Buddha when I was here, a practitioner asked me, ‘Do even people in the state of great practice fall into cause and effect, or not?’ I answered, 'No'. And that is when it occurred. Please, Master, say for me a word of transformation. I long to be rid of the body of a wild fox." When Master Daichi replies "Do not be unclear about cause and effect," the old man is relieved, and then asks for a monk's funeral. The next day, Master Daichi leads the monks to the foot of a rock on the mountain behind the temple, and picking out a dead fox with a stick, they cremate it according to the formal method.

What are the multiple moral and contradictory messages of this koan? Why a fox? Why not to become a fox?

There are countless Ch'an/Zen medieval commentaries on the wild fox koan. Dogen offers several treatises on Hyakujo and the Wild Fox. He first gives a conventional interpretation of the koan, but towards the end of his life, he shifts towards a more imaginative and supernatural interpretation. Why did Dogen change his tune?

I go to Hein (1999) to understand these fox-persons in the koan. In Japanese lore, foxes are demonic (the nine-tailed fox) and shape-shifting tricksters. One can be possessed by the fox. They populate folklore and popular texts. (Bathgate 2004), so there actually is a connection between my fox wedding and jesse's wild fox. Hein reviews the sermon of Chinese abbot Pai-chang Huai-hai. In this sermon, the non-human monk confesses to fei-jen, the term for spirit possession in East Asian folklore, indicative of the six realms of transmigration. The fox/monk is liberated by the "turning word" of the abbot who responds that even the enlightened must submit to causation. Now liberated, his fox corpse is found on the temple grounds and he is given a monk's funeral at the abbot's instruction. The fox, Hein offers, is a door between realms, both philosophical and folkloric. In this first rendition, Hein says that the koan might be less about metaphysics of causality, as it seems to be, but rather about supernaturalism and ritualism. This is about the fox-monk funeral that the abbot conducts. You know already that I follow Dogen on this, from a formal reflection on causation to an interest on metamophosis and ritual action.

And why does Pai-chang receive a blow from his student after successfully cremating the old monk? The first of a Zen ritual of insubordination. A wake up?

Was jesse boxing my ears? Am I already a fox? Have I been a fox for these many years, possessed by the mistake of causation? In Turning Word, James Ishmael Ford reminds us, We are what we do. Reflecting as a UU/Buddhist minister on this koan, he says, "whatever we are, unless we notice and take corrective action, we just become more of it."

Shift, regret, act. Now.

-----

References

Bathgate, Michael, The Fox's Craft in Japanese Religion and Culture: Shapeshifters, Transformations, and Duplicities, Routledge, 2004

Heine, Steven, Putting The ``Fox'' Back in The ``Wild Fox Kōan'': The Intersection of Philosophical and Popular Religious Elements in The Ch'an/Zen Kōan Tradition, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies Vol. 56, No. 2 (Dec., 1996), pp. 257-317

__________ Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Kōan, University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

There are countless Ch'an/Zen medieval commentaries on the wild fox koan. Dogen offers several treatises on Hyakujo and the Wild Fox. He first gives a conventional interpretation of the koan, but towards the end of his life, he shifts towards a more imaginative and supernatural interpretation. Why did Dogen change his tune?

I go to Hein (1999) to understand these fox-persons in the koan. In Japanese lore, foxes are demonic (the nine-tailed fox) and shape-shifting tricksters. One can be possessed by the fox. They populate folklore and popular texts. (Bathgate 2004), so there actually is a connection between my fox wedding and jesse's wild fox. Hein reviews the sermon of Chinese abbot Pai-chang Huai-hai. In this sermon, the non-human monk confesses to fei-jen, the term for spirit possession in East Asian folklore, indicative of the six realms of transmigration. The fox/monk is liberated by the "turning word" of the abbot who responds that even the enlightened must submit to causation. Now liberated, his fox corpse is found on the temple grounds and he is given a monk's funeral at the abbot's instruction. The fox, Hein offers, is a door between realms, both philosophical and folkloric. In this first rendition, Hein says that the koan might be less about metaphysics of causality, as it seems to be, but rather about supernaturalism and ritualism. This is about the fox-monk funeral that the abbot conducts. You know already that I follow Dogen on this, from a formal reflection on causation to an interest on metamophosis and ritual action.

And why does Pai-chang receive a blow from his student after successfully cremating the old monk? The first of a Zen ritual of insubordination. A wake up?

Was jesse boxing my ears? Am I already a fox? Have I been a fox for these many years, possessed by the mistake of causation? In Turning Word, James Ishmael Ford reminds us, We are what we do. Reflecting as a UU/Buddhist minister on this koan, he says, "whatever we are, unless we notice and take corrective action, we just become more of it."

Shift, regret, act. Now.

-----

References

Bathgate, Michael, The Fox's Craft in Japanese Religion and Culture: Shapeshifters, Transformations, and Duplicities, Routledge, 2004

Heine, Steven, Putting The ``Fox'' Back in The ``Wild Fox Kōan'': The Intersection of Philosophical and Popular Religious Elements in The Ch'an/Zen Kōan Tradition, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies Vol. 56, No. 2 (Dec., 1996), pp. 257-317

__________ Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Kōan, University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed