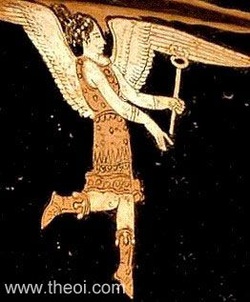

Hypnos (sleep) twin brother of Thanatos (death)

Hypnos (sleep) twin brother of Thanatos (death) Epiphany or epiphaneia, ἐπιφάνεια, means "manifestation." William Harrison argues that epiphany dreams among the Greeks and Romans consist of "the appearance to the dreamer of an authoritative personage who may be divine or represent a god, and this figure conveys instructions or information." (4) Since I am interested in epiphany dreams, I turn to the prolific ancient and contemporary scholars of Greco-Roman Antiquity. I start with Homer in 500 BCE to Late Antiquity in 600 C.E.. Greeks spoke of "seeing" their dreams (Dodds, 105), and those they saw were often gods.

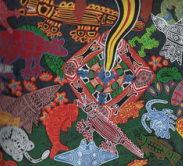

I risk a leap here, connecting dream statues in Cambodia with dream statues at such a disparate time-space, but Greco-Roman dreaming reflects on the mimesis of dreams, god-visits and their dream statues. Who can resist a quaff of its ambrosia αμβροσία? (In time, we return to the devas and asuras churning the sea of milk for the amrit of immortality, and thus the Indic/Buddhist dream stories of Angkor Wat.)

The Greek genealogy of sleep starts with Hypnos, son of Nyx (goddess of night) and Erebus (ruler of dark regions of underworld). Hypno's twin brother is Thanatos, god of death. Hypnos fathers the Oneiroi: Morpheus, Phobetor (known as Icelus to the gods) and Phantasos. These oneiroi by various accounts, are dark winged daemons, perhaps bats who fly through the gates of horn or ivory to unwary sleepers.

I risk a leap here, connecting dream statues in Cambodia with dream statues at such a disparate time-space, but Greco-Roman dreaming reflects on the mimesis of dreams, god-visits and their dream statues. Who can resist a quaff of its ambrosia αμβροσία? (In time, we return to the devas and asuras churning the sea of milk for the amrit of immortality, and thus the Indic/Buddhist dream stories of Angkor Wat.)

The Greek genealogy of sleep starts with Hypnos, son of Nyx (goddess of night) and Erebus (ruler of dark regions of underworld). Hypno's twin brother is Thanatos, god of death. Hypnos fathers the Oneiroi: Morpheus, Phobetor (known as Icelus to the gods) and Phantasos. These oneiroi by various accounts, are dark winged daemons, perhaps bats who fly through the gates of horn or ivory to unwary sleepers.

The space of dreams, demos oneiron

Patricia Cox in Dreams of Late Antiquity reflects on the recursive nature of dreams -- images inside images. In order to understand later Greek analysis of dreams, you must know the Hellenic texts from which they are derived. Dreams inside dreams inside dreams.

Through Homer's Odyssey we learn of the ancient Greek dream territory, the demos oneiron that borders the land of the dead. To get to this imaginal space you must first cross the Okeanos (Oceanus) river that encircles the "real." This river (not unlike the Jordan), is the boundary of cosmic space. Beyond is a fantastical place, offers Brelick, the reversal of cosmic order that mirrors the other (p 298, cited in Cox, p 15). This demos oneiron, a third space between the living and the dead, is translated as both the "village" or the "people" of dreams. As a territory, the demos oneiron has two gates. Homer sets them in Penelope's interpretation of her own dream that Odysseus was finally returning home.

Through Homer's Odyssey we learn of the ancient Greek dream territory, the demos oneiron that borders the land of the dead. To get to this imaginal space you must first cross the Okeanos (Oceanus) river that encircles the "real." This river (not unlike the Jordan), is the boundary of cosmic space. Beyond is a fantastical place, offers Brelick, the reversal of cosmic order that mirrors the other (p 298, cited in Cox, p 15). This demos oneiron, a third space between the living and the dead, is translated as both the "village" or the "people" of dreams. As a territory, the demos oneiron has two gates. Homer sets them in Penelope's interpretation of her own dream that Odysseus was finally returning home.

Truly dreams are by nature perplexing and full of messages which are hard to interpret; nor by any means will everything [in them] come true for mortals. For there are two gates of insubstantial dreams; one [pair] is wrought of horn and one of ivory. Of these, [the dreams] which come through [the gate of] sawn ivory are dangerous to believe, for they bring messages which will not issue in deeds; but [the dreams] which come forth through [the gate of] polished horn, these have power in reality, whenever any mortal sees them.

cf Od 19.560-67. cited in Cox, 1994, p 15

This distinction between ivory and horn is commonly interpreted as a Greek play on words in which the word for ivory is similar to deception and horn, fulfill. Later, Virgil will return to the gates of ivory and horn, distinguishing them as false and true more forcefully than Homer intended, and thus, according to Cox, laying the groundwork for the future of oneirokritica from Artemidorus forward. (Cox, p 26).

For later Roman authors - Ovid and Virgil - this insubstantial dream territory is even more chthonic and malevolent - a dark earthen underworld veiled in mist and fog, webbed with langorous phantasms. Virgil sets the dreamworld with a great tree draped with "unsolid dreams" like bats beneath the foliage.

Ultimately Cox chooses "people," and certainly, oneiroi have been characterized as sons of dark mothers - Nyx (night), or Gaia (earth) and black-winged themselves. Thus, they are divine images, always disguised, and as Penelope says, insubstantial, fleeting, that yet leave an emotional tangle. (See Kessel on this.)

For later Roman authors - Ovid and Virgil - this insubstantial dream territory is even more chthonic and malevolent - a dark earthen underworld veiled in mist and fog, webbed with langorous phantasms. Virgil sets the dreamworld with a great tree draped with "unsolid dreams" like bats beneath the foliage.

Ultimately Cox chooses "people," and certainly, oneiroi have been characterized as sons of dark mothers - Nyx (night), or Gaia (earth) and black-winged themselves. Thus, they are divine images, always disguised, and as Penelope says, insubstantial, fleeting, that yet leave an emotional tangle. (See Kessel on this.)

The morph of dreams

In Ovid's Metamorphosis myths entangle with dreams and we are struck by the ways god's appear as not-themselves. Thus, through Morpheus (a form-being), the god of dreams, son of Hypnos, a message is sent about the death of a loved one, in which truth and half-truth are blurred. And now, Morpheus = Morphine, the anti-dote to pain; he is the anti-king of the Matrix a computer-generated dream-space. Fishburn-Morpheus is immortalized by his wry greeting to Neo, "welcome to the desert of the real," which Zizek applies to post-911 America. This desert of the real is populated by somnambulent half-persons living in a Meta-morph-psychosis.

For a longer depiction of sleep, dreams, and its 'space of appearance', we drop in on Iris, rainbow messenger of Hera-June (wisdom), as she visits Somnus, Roman god of sleep to "bid him send a dream of Ceyx drowned to break the tidings to Alcyone." Somnus sends out Morpheus.

This thoughtful blog on Ovid's Metamorphosis depicts and then reflects on Iris' visit to Somnus. Iris is visual relief to the thanatos of sleep, and the half-truths of the dream.

There are a plenitude of epiphany dreams. In more famous cases, Heroditus refers to the dreams of King Xerxes who was visited by a tall, fine-looking visitor who told him to reverse his policy and invade Greece. Or consider Socrates' dream of a "fine and beautiful women" who told him which day he would be executed (Harrison 25).We have many questions here. First, were the plenitude of epiphanies "true"? (Did the gods appear?) Or was there a conventional narrative? How does one determine the true epiphanies from conventional forms? How can we detect the gate of ivory from the gate of horn?

And finally we investigate the particular nature of statue-epiphanies. In what forms do the gods appear? How do the Greeks and Romans distinguish between form and representation? How does one sacralize that which humans have made? How does it take on life? This is also a question posed about other religious relics- Buddha statues, Chinese relics -- and so we will move slowly East towards that other Orient.

We will tarry on these questions in the next post.

For a longer depiction of sleep, dreams, and its 'space of appearance', we drop in on Iris, rainbow messenger of Hera-June (wisdom), as she visits Somnus, Roman god of sleep to "bid him send a dream of Ceyx drowned to break the tidings to Alcyone." Somnus sends out Morpheus.

This thoughtful blog on Ovid's Metamorphosis depicts and then reflects on Iris' visit to Somnus. Iris is visual relief to the thanatos of sleep, and the half-truths of the dream.

There are a plenitude of epiphany dreams. In more famous cases, Heroditus refers to the dreams of King Xerxes who was visited by a tall, fine-looking visitor who told him to reverse his policy and invade Greece. Or consider Socrates' dream of a "fine and beautiful women" who told him which day he would be executed (Harrison 25).We have many questions here. First, were the plenitude of epiphanies "true"? (Did the gods appear?) Or was there a conventional narrative? How does one determine the true epiphanies from conventional forms? How can we detect the gate of ivory from the gate of horn?

And finally we investigate the particular nature of statue-epiphanies. In what forms do the gods appear? How do the Greeks and Romans distinguish between form and representation? How does one sacralize that which humans have made? How does it take on life? This is also a question posed about other religious relics- Buddha statues, Chinese relics -- and so we will move slowly East towards that other Orient.

We will tarry on these questions in the next post.

Here is the full translation of the Ovid story copied below.

Then Iris, in her thousand hues enrobed traced through the sky her arching bow and reached the cloud-hid palace of the drowsy king. Near the Cimmerii (Cimmerians) a cavern lies deep in the hollow of a mountainside, the home and sanctuary of lazy Somnus (Sleep), where Phoebus' [the Sun's] beams can never reach at morn or noon or eve, but cloudy vapours rise in doubtful twilight; there no wakeful cock crows summons Aurora [Eos the Dawn], no guarding hound the silence breaks, nor goose, a keener guard; no creature wild or tame is heard, no sound of human clamour and no rustling branch. There silence dwells: only the lazy stream of Lethe 'neath the rock with whisper low o'er pebbly shallows trickling lulls to sleep. Before the cavern's mouth lush poppies grow and countless herbs, from whose bland essences a drowsy infusion dewy Nox [Nyx, Night] distils and sprinkles sleep across the darkening world. No doors are there for fear a hinge should creak, no janitor before the entrance stands, but in the midst a high-raised couch is set of ebony, sable and downy-soft, and covered with a dusky counterpane, whereon the god, relaxed in languor, lies. Around him everywhere in various guise lie empty Somnia [Oneiroi, Dreams], countless as ears of corn at harvest time or sands cast on the shore or leaves that fall upon the forest floor.

There Iris entered, brushing the Somnia (Dreams) aside, and the bright sudden radiance of her robe lit up the hallowed place; slowly the god his heavy eyelids raised, and sinking back time after time, his languid drooping head nodding upon his chest, at last he shook himself out of himself, and leaning up he recognized her and asked why she came, and she replied: ‘Somnus [Hypnos, Sleep], quietest of the gods, Somnus, peace of all the world, balm of the soul, who drives care away, who gives ease to weary limbs after the hard day's toil and strength renewed to meet the morrow's tasks, bid now thy Somnia (Dreams), whose perfect mimicry matches the truth, in Ceyx's likeness formed appear in Trachis to Alcyone and feign the shipwreck and her dear love drowned. So Juno [Hera] orders.’

Then, her task performed, Iris departed, for she could no more endure the power of Somnus (Sleep), as drowsiness stole seeping through her frame, and fled away back o'er the arching rainbow as she came. The father Somnus chose from among his sons, his thronging thousand sons, one who in skill excelled to imitate the human form; Morpheus his name, than whom none can present more cunningly the features, gait and speech of men, their wonted clothes and turn of phrase. He mirrors only men; another forms the beasts and birds and the long sliding snakes. The gods have named him Icelos; here below the tribe of mortals call him Phobetor. A third, excelling in an art diverse, is Phantasos; he wears the cheating shapes of earth, rocks, water, trees--inanimate things. To kings and chieftains these at night display their phantom features; other dreams will roam among the people, haunting common folk. All these dream-brothers the old god passed by and chose Morpheus alone to undertake Thaumantias' [Iris'] commands; then in sweet drowsiness on his high couch he sank his head to sleep."

References

Brelich, "The Place of Dreams in the Religious World Concept of the Greeks," In The Dream and Human Society, 293-401, Eds G.E. Von Greunbaum and R. Caillois, Berkeley: U of California Press, 1966

Cox Miller, Patricia Dreams in Late Antiquity. Studies in the Imagination of a Culture, Princeton University Press, 1994

Crites, Stephen, Angels we have heard, In Religion as Story, Ed James B. Wiggins, New York: Harper and Row, 1975, 137-47.

Dodds, E. R. The Greeks and the Irrational, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951

Graf, F, Epiphany, in H. Cancit, and H, Schneider (eds) Brill's New Pauly, Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, Vol IV. Leiden: 1122-3, 2010

Harris, William V. Dreams and Experience Classical Antiquity, Harvard University Press, 2009

Kessels, A.H.M, Studies on the Dreams in Greek Literature, Utrecht: HES Publication, 1978

Lane Fox, R. Pagans and Christians, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987

Pfister, F. Epiphanie, in RE supp IV (1924) cols 277-323

Platt, Verity Facing the Gods. Epiphany and Representation in Graeco-Roman Art, Literature and Religion, Cambridge University Press,

Cox Miller, Patricia Dreams in Late Antiquity. Studies in the Imagination of a Culture, Princeton University Press, 1994

Crites, Stephen, Angels we have heard, In Religion as Story, Ed James B. Wiggins, New York: Harper and Row, 1975, 137-47.

Dodds, E. R. The Greeks and the Irrational, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951

Graf, F, Epiphany, in H. Cancit, and H, Schneider (eds) Brill's New Pauly, Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, Vol IV. Leiden: 1122-3, 2010

Harris, William V. Dreams and Experience Classical Antiquity, Harvard University Press, 2009

Kessels, A.H.M, Studies on the Dreams in Greek Literature, Utrecht: HES Publication, 1978

Lane Fox, R. Pagans and Christians, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987

Pfister, F. Epiphanie, in RE supp IV (1924) cols 277-323

Platt, Verity Facing the Gods. Epiphany and Representation in Graeco-Roman Art, Literature and Religion, Cambridge University Press,

RSS Feed

RSS Feed