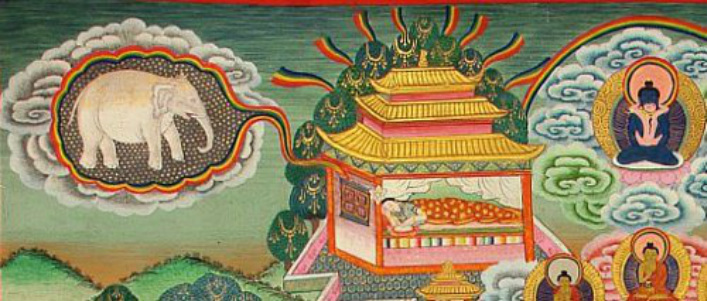

Queen Māyā of Sakya (Māyādevī) conception dream

On a full moon night of a midsummer festival, Queen Māyā retired to her bedroom and fell into a deep sleep. In her dream, she was lifted by four devas (spirits) to Lake Anotatta in the white capped Himalayas. There, they bathed, perfumed and bedecked her with flowers. A white bull elephant clutching a white lotus flower in its trunk appeared and circumnambulated her three times. Then, he struck her right side and disappeared into her. The queen awoke in a blaze of energy and relayed the dream to the king. Since the elephant is a symbol of greatness, he summoned 64 brahmans who told him that his son would be a world conqueror or world renouncer.

Conception dreams are common throughout Buddhism and recorded in biographical literature of famous bodhisattvas and siddhas. Depictions of Queen Maya's dream are some of the earliest representations of Buddhism in iconography (Young, 2003, 167). Not to be outdone, the future mother of Mahaviras, Jain Queen Trishala is also visited by a white elephant in her conception dream. This is followed by thirteen auspicious dreams. One could say much on the topic of conception here, how women's bodies require visitations from angels, elephants, lions, and goddesses (!) to announce - and impregnate women - for a holy boy. Young notes that the Hindu Palija takas are rich with the dreams of women (166).

Let us return to Queen Maya.

When she was nearly due, she travelled to a sacred grove near her parent's home. In Lumbini, when labor was upon her, she caught a blossoming branch of a tree and painlessly produced the child. (Like Maryam in Islamic tradition, holy trees -- and their spirits--assist the birthing woman.) The Flower Ornament Sutra depicts it thus:

As Lady Maya leaned against the holy fig tree, all the world rulers, gods and goddesses... and all the other beings... were bathed in the glorious radiance of Maya's body .... All the lights in the billion-world universe were eclipsed by Maya's light. The lights emanating from all her pores... pervaded everywhere, extinguishing all suffering... illuminating the universe (Shaw 1998).

A few days later, she was dead. (All previous mothers died after giving birth to Buddhas.) But she watched and instructed her son from the heavens. Buddha too can traverse these three realms.

Shakyamuni's five dreams

Siddhārtha Gautama's father, wife and aunt all share dreams portending his departure. Gautama himself has several dreams. In one, "He saw millions of beings carried away by the current of a river. He crossed this river and made a vessel to carry others across" (cf Young, 31). More famous are his five dreams before the world-trembling event of his enlightenment, itself so dream-like.

Young argues that Buddhists hold to an the activating potential of dreams. An example occurs in the jataka tale in the Divyavadana when Gautama Buddha as a Brahman in a previous meets Dipamkara, a former buddha who predicts his future buddhahood (1999, 26). Here, the young Gautama-as-Brahman has ten dreams (he drinks the great ocean, flies through the air, held the sun and moon, is the king's charioteer, saw ascetics, white elephants, geese, lions, a great rock and mountains). He takes them to an ascetic, but they cannot be interpreted. He learns that only Dipamkara the buddha can interpret his dreams. These dreams resonate with Queen Maya's conception dream, King Suddhodana's dream of his son's departure and Buddha's five dreams. Through these dreams, his own route to buddhahood is predicted and projected. And as we learn from the Divyavadana, only those with superior ability can correctly interpret dreams.

But let us know the five dreams and their interpretation:

Monks, before the Tathāgata, the Arahat, the Fully Enlightened One attained enlightenment, while he was still a bodhisatta, five great dreams appeared to him. What five?

Young argues that Buddhists hold to an the activating potential of dreams. An example occurs in the jataka tale in the Divyavadana when Gautama Buddha as a Brahman in a previous meets Dipamkara, a former buddha who predicts his future buddhahood (1999, 26). Here, the young Gautama-as-Brahman has ten dreams (he drinks the great ocean, flies through the air, held the sun and moon, is the king's charioteer, saw ascetics, white elephants, geese, lions, a great rock and mountains). He takes them to an ascetic, but they cannot be interpreted. He learns that only Dipamkara the buddha can interpret his dreams. These dreams resonate with Queen Maya's conception dream, King Suddhodana's dream of his son's departure and Buddha's five dreams. Through these dreams, his own route to buddhahood is predicted and projected. And as we learn from the Divyavadana, only those with superior ability can correctly interpret dreams.

But let us know the five dreams and their interpretation:

Monks, before the Tathāgata, the Arahat, the Fully Enlightened One attained enlightenment, while he was still a bodhisatta, five great dreams appeared to him. What five?

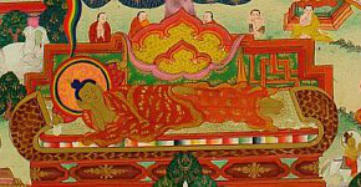

He dreamt that this mighty earth was his great bedstead; the Himālaya, king of mountains, was his pillow; his left hand rested on the eastern sea, his right hand on the western sea; his two feet on the southern sea. This, monks, was the first dream that appeared to the Tathāgata while he was still a bodhisatta.

Again, he dreamt that from his navel arose a kind of grass called tiriyā and continued growing until it touched the clouds. This, monks, was the second great dream....

Again, he dreamt that white worms with black heads crawled on his legs up to his knees, covering them. This, monks, was the third great dream....

Again, he dreamt that four birds of different colours came from the four directions, fell at his feet and turned all white. This, monks, was the fourth great dream....

Again, he dreamt that he climbed up a huge mountain of dung without being soiled by the dung. This, monks, was the fifth great dream....

Now when the Tathāgata, while still a bodhisatta, dreamt that the mighty earth was his bedstead, the Himālaya, king of mountains, his pillow ... this first dream was a sign that he would awaken to unsurpassed, perfect enlightenment.

When he dreamt of the tiriyā grass growing from his navel up to the clouds, this second great dream was a sign that he would fully understand the Noble Eightfold Path and would proclaim it well among devas and humans.

When he dreamt of the white worms with black heads crawling on his legs up to his knees and covering them, this third great dream was a sign that many white-clad householders would go for refuge to the Tathāgata until the end of their lives.

When he dreamt of four birds of different colours coming from all four directions and, falling at his feet, turning white, this fourth great dream was a sign that members of the four castes— nobles, brahmins, commoners and menials—would go forth into homelessness in the Doctrine and Discipline taught by the Tathāgata and would realize the unsurpassed liberation.

When he dreamt of climbing up a huge mountain of dung without being soiled by it, this fifth great dream was a sign that the Tathāgata would receive many gifts of robes, alms-food, dwellings and medicines, and he would make use of them without being tied to them, without being infatuated with them, without being committed to them, seeing the danger and knowing the escape.

These are the five great dreams that appeared to the Tathāgata, the Arahat, the Fully Enlightenment One, before he attained enlightenment, while he was still a bodhisatta.

Aṅguttara Nikāya An Anthology, Part II, Selected and translated by Nyanaponika Thera and Bhikku Bodhi, BPS Online Edition, 2008, pg 1

The dream worlds of South Asia are verdant with imagery, profound and quixotic. In the Kurma Purana, this kalpa (eon) is a great ocean in which Brahma (or Vishnu) is sleeping on the coil of a naga (snake). He dreams that a lotus grows out of his navel (see the Buddha's dream below) from which arises all that exists. From this dream, our reality. Wendy O'Flaherty's Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities which traverses a wide South Indian terrain (1984) indicates that the dreams of Buddha and their interpretations shift interpretation from a Brahmanical context in which they had negative meaning to new positive angles. From these dreams emerges a Buddhist dream theory, thin in Theravada, but rich in Mahayana. They come to one from a repository that transcends time. From birth to birth, the dreams show up as replays in the next-born Buddha. Because these dreams are repeated in different texts, Young (1999, 31) argues that Buddha's dreams offer a map to the dream world of potential buddhas - signs to leave home. They can point the direction towards enlightenment. Most importantly, significant dreams that signal the presence of other realms need to be interpreted and understood within a Buddhist context. Thus, spiritual adepts can pass back and forth between realms.

Since the dreamers I'm following in Cambodia follow the Theravadan tradition, I am less focused on the Vajrayana tradition of dream yoga, which is intimidating in its authority over our dream life. The Cambodian dream worlds intersect at two points: at rebirth when the returning one asks to inhabit a woman's womb, and after death, when a loved one has instructions early after death, on an unfinished task or is unable to complete the transition to rebirth. There doesn't seem to be much literature on this arc of dreaming, a fascinating continuity.

Since the dreamers I'm following in Cambodia follow the Theravadan tradition, I am less focused on the Vajrayana tradition of dream yoga, which is intimidating in its authority over our dream life. The Cambodian dream worlds intersect at two points: at rebirth when the returning one asks to inhabit a woman's womb, and after death, when a loved one has instructions early after death, on an unfinished task or is unable to complete the transition to rebirth. There doesn't seem to be much literature on this arc of dreaming, a fascinating continuity.

References

O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger, Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities, University of Chicago Press, 1984

Shaw, Miranda, Blessed are Birth-Givers, Parabola 1998.

________Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. 2006, p. 51

Thundy, Zacharias P., Buddha and Christ: Nativity Stories and Indian Traditions, Brill Academic Pub, 1993

Young, Serenity, Dreams, In South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka edited by Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann Mills, Taylor & Francis, 2003, 166-169

____________Dreaming the Lotus. Buddhist Dream Narrative, Imagery and Practice, Wisdom Publications, 1999

O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger, Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities, University of Chicago Press, 1984

Shaw, Miranda, Blessed are Birth-Givers, Parabola 1998.

________Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. 2006, p. 51

Thundy, Zacharias P., Buddha and Christ: Nativity Stories and Indian Traditions, Brill Academic Pub, 1993

Young, Serenity, Dreams, In South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka edited by Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann Mills, Taylor & Francis, 2003, 166-169

____________Dreaming the Lotus. Buddhist Dream Narrative, Imagery and Practice, Wisdom Publications, 1999

RSS Feed

RSS Feed