I first became interested in the Muslim dreamers through Amira Mittermaier's Dreams that Matter, a rich ethnography of visionary dreams in contemporary Egypt. She offers a mixture of responses to this particular form of visionary dreaming. Her first chapter begins with a dream interpreted on an Egyptian TV show. The caller referred to a moon nursing a boy and the shaykh on the show declared that the madhi had been born, a claim that took the show off the air. (I wonder if, in 2011, that claim circulated again on the streets of Cairo.) Mittermaier lets us know that dream work is complicated in Egypt and we should refrain from post-9/11 inclinations to a political-Islam-form of Orientalism. She meets with Egyptian Freudians and rationalist reformers, but lingers among Sufi devotees of several shaykhs who claim that their dreams arrive from the Prophet or elsewhere. As dream interpretation is common in Islam, this is not unusual, but Mittermaier's interlocutors mix-match religious & Westerner psychological approaches so that the dreaming self occupies a permeable body.

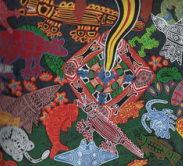

Mittermaier refers to her work as an "anthropology of the imagination" and she considers the imagination in this case from a Islamic perspective. She relies on a Muslim genealogy of the imagination from medieval Sufi scholars al-Ghazali and Ibn al-'Arabi in particular who consider the imagination (al-khayal) a realm between the spiritual and material, the visible and invisible, God and humans.

This intermediate space is often called the barzakh, literally, isthmus. It is most often considered the space in which those who have died wait for the resurrection, a sort of purgatory. But Sufi mystics such as Ibn 'Arabi have given it a less literal meaning. For a lyrical depiction of the barzakh and dream life, I'd refer anyone to the Stefania Pandofo's phenomenal Moroccan ethnography, Impasse of the Angels. One can easily become lost in her labyrinthine language, but step out and return. She counterposes Qur'anic scholar and dream interpreter Si Lhassan's theory of dreaming with Freud, Lacan and Ibn-'Arabi. For Si Lhassan, says Pandolfo, dreaming is an "'exit', an otherworldly journey, an encounter, and of knowledge passed on, between the wandering ruh of the dreamer and other errant souls, of the living and the dead" (Pandolfo, 1997, 9).

Egyptian Nobel Prize novelist Naguib Mahfouz traversed a kind of barzakh before his death in 2006. When he was already suffering from blinding diabetes at 80, he was stabbed in the neck in a religiously motivated assassination attempt. He recovered without full use of his right hand. Stricken by this incident, he published over 300 of his dreams following a Muslim interest in dream life, and submitted Dreams of Convalescence to a Cario magazine. The dreams are short, usually one paragraph depictions of his nightly travels. These were translated and published as The Dreams (2004) and Dreams of Departure (2006). Some dreams rehearse or reverse his experience, many are about women he had known, most occur in the quotidian of his life.

What was Mahfouz's intent in publishing them? Dream work is the only authentic form of divination in Islam. Who is Mahfouz to his dreams and what intermediate space might we find there? Mahfouz's Book Of Dreams was reviewed on NPR

What draws us to other's raw psychic material, dreams untapped and only slightly interpreted? There is a genre of this work, often of saints (Don Bosco has a book of dreams) and writers such as Georges Perec's La Boutique Obscure: 124 Dreams. There is also a trend of the dreams of scientists that lead to discovery, but this does not constitute a corpus.

On this dreams of "elsewhere" - I'll be taking up Obeyeskere's The Awakened Ones: Phenomenology of Visionary Experience. Obeyeskere, a Sri Lankan, and emeritus anthropologist at Princeton, uses psychoanalysis to investigate the relationship between cultural and personal symbolism and religious experience. In this latest work, which meanders over 400 pages, he considers nonrational visionary experience, comparing Buddha's enlightenment experience to Western Christian mystics and spiritualists. What is this "dream ego" he offers up to us? How does Nietzsche's epistemology inflect his notions of nonrational knowing? Why does this matter?

Mittermaier refers to her work as an "anthropology of the imagination" and she considers the imagination in this case from a Islamic perspective. She relies on a Muslim genealogy of the imagination from medieval Sufi scholars al-Ghazali and Ibn al-'Arabi in particular who consider the imagination (al-khayal) a realm between the spiritual and material, the visible and invisible, God and humans.

This intermediate space is often called the barzakh, literally, isthmus. It is most often considered the space in which those who have died wait for the resurrection, a sort of purgatory. But Sufi mystics such as Ibn 'Arabi have given it a less literal meaning. For a lyrical depiction of the barzakh and dream life, I'd refer anyone to the Stefania Pandofo's phenomenal Moroccan ethnography, Impasse of the Angels. One can easily become lost in her labyrinthine language, but step out and return. She counterposes Qur'anic scholar and dream interpreter Si Lhassan's theory of dreaming with Freud, Lacan and Ibn-'Arabi. For Si Lhassan, says Pandolfo, dreaming is an "'exit', an otherworldly journey, an encounter, and of knowledge passed on, between the wandering ruh of the dreamer and other errant souls, of the living and the dead" (Pandolfo, 1997, 9).

Egyptian Nobel Prize novelist Naguib Mahfouz traversed a kind of barzakh before his death in 2006. When he was already suffering from blinding diabetes at 80, he was stabbed in the neck in a religiously motivated assassination attempt. He recovered without full use of his right hand. Stricken by this incident, he published over 300 of his dreams following a Muslim interest in dream life, and submitted Dreams of Convalescence to a Cario magazine. The dreams are short, usually one paragraph depictions of his nightly travels. These were translated and published as The Dreams (2004) and Dreams of Departure (2006). Some dreams rehearse or reverse his experience, many are about women he had known, most occur in the quotidian of his life.

What was Mahfouz's intent in publishing them? Dream work is the only authentic form of divination in Islam. Who is Mahfouz to his dreams and what intermediate space might we find there? Mahfouz's Book Of Dreams was reviewed on NPR

What draws us to other's raw psychic material, dreams untapped and only slightly interpreted? There is a genre of this work, often of saints (Don Bosco has a book of dreams) and writers such as Georges Perec's La Boutique Obscure: 124 Dreams. There is also a trend of the dreams of scientists that lead to discovery, but this does not constitute a corpus.

On this dreams of "elsewhere" - I'll be taking up Obeyeskere's The Awakened Ones: Phenomenology of Visionary Experience. Obeyeskere, a Sri Lankan, and emeritus anthropologist at Princeton, uses psychoanalysis to investigate the relationship between cultural and personal symbolism and religious experience. In this latest work, which meanders over 400 pages, he considers nonrational visionary experience, comparing Buddha's enlightenment experience to Western Christian mystics and spiritualists. What is this "dream ego" he offers up to us? How does Nietzsche's epistemology inflect his notions of nonrational knowing? Why does this matter?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed