I want to interrogate the Oikouménē, but let's just call it the ecumene. We know the ecumene as the “whole inhabited earth," but which bodies, what persons, inhabit it? Do we also include ethereal bodies – hungry ghosts, boramey, apparitions of Mary – as social beings? Sociologist Avery Gordon has noted that, "the ghost is not simply dead or a missing person, but a social figure" (Gordon 2008, 2 ).

Latour (2005) has pressed us to "reassemble the social," to rethink what we mean by this over-used term. I ask, how can we “reassemble our ecumenes” to be more elastic with the boundaries of our real, to learn different ways of being, so that the worldviews of those we study, advocate for -- and resist --are constitutive of a range of personhoods? I will suggest that we must account for other bodies: bodies of what we might call entities or actants. Some are gendered, but in multiple ways – asexual, dimorphic, hermaphrodite – some are not. Some are invisible, spectral, some appallingly visual, others are inorganic. Some entities occupy other bodies; some are aggregates of other entities. I am interested in whether, or how, these bodies do what we humans call knowing and acting, but in different ways. This has methodological implications, and I focus here on Cambodia's spectral other-than-human world.

In refugee camps, living rooms, and among friends, I’d heard personal refugee accounts of those who had endured Cambodia’s “travesty of history” from 1975-1979 when the Khmer Rouge walked into the capital Phnom Penh and declared “Year Zero, “ inaugurating a revolutionary communist regime in which a quarter of the population was exterminated or died of malnutrition. While all cities were evacuated, the most stunning was Phnom Penh, where members of the former regime were assassinated or sent to interrogation centers such as Toul Sleng. Choeung Eck, a field of mass graves outside of town, is the most notorious of the hundreds of “killing fields.” The regime ended in early 1979 when newly socialist Vietnamese invaded, occupying Cambodia for a decade until the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1991.

This political world -- saturated with violence -- is set within a Cambodian Theravada worldview. Interaction with supernatural creatures: boramay, neak ta, and preta, is integral to Cambodian cosmology. Boramey (or parami) are spirits associated with Buddhism and manifest benevolent supernatural power. Boramey can be the attribute of a statue, such as the Leper King (Hang, Gamlan and Deb 2004) or a manifestation of mytho-historic figures such as generals or kings who possess a medium (Bertrand 2001). The boramey often speak through dreams. Neak ta, on the other hand, are guardians of the land. Friends noted that during the Khmer Rouge era, neak ta were disrupted and the palm trees would not bear fruit. Preta, hungry ghosts, inhabited desecrated holy spaces such as Buddhist wats used for storage and torture (Chandler 2007). The “killing fields” were saturated with phantasmic terror, populated with roaming preta because the near-dead had been violated, and when dead, were not properly buried (Levine 2010). They could not continue on to the next life.

Are these creatures locked into Cambodian worldviews? Do they slip out of their "representation” and visit others? I had encounters with preta and boramey in my time with Cambodians both in Asia and the United States. My spooky meet-up with a preta occurred on a travel seminar to Phnom Penh coordinated through San Francisco Theological Seminary in 1992. A decade after the Khmer Rouge departure, the city still seemed bedraggled and slightly surreal, residents four-to-a-bicycle plying Monivong Avenue, dark nights interrupted by generator-driven pools of light. Bats hung like overripe fruit in the naked trees near the UN Transitional Authority compound. Even the most prominent wats were derelict and forlorn, decapitated heads of the Buddha laid out near their stupas. So it was not entirely surprising that after a visit to Choeung Ek, my American roommate looked wan. She sat at the corner of her bed and shot me a nervous glance, “When you lie down, do you see anything?” When I said no, she hesitated, “When I lie down, I see three men with machine guns at the foot of my bed.” Chills shot up my back. The room suddenly felt ominous and cold. We improvised an exorcism, and when we ran out of ideas, we went to sleep. I was startled awake by the pressure of a ghostly body on top of me. I plopped a pillow over my head, praying feverishly, until—whoosh—the room felt clear. “A preta,” mused a Cambodian friend when I relayed the story later. There seemed to be many preta prowling around Phnom Penh.

Ghosts, neak ta, devata as inhabitants of our worlds, are social actors often denied a voice in the stories we tell about war, survival, and post conflict, even though they are everywhere. In theological work on conflict, I don’t often hear about prophetic dreams and signs that help survivors map catastrophic events, or statues, amulets or tatoos that protect border crossings, or apparitions of Mary or Kwan Yin who appear to Vietnamese boat people when their engines stall or pirates trail them. What do we do with Jesus appearing to a Buddhist prisoner of the Khmer Rouge with advice that saves him? Family stories like these disappear from the “refugee narrative” upon arrival in the United States, and they are not (often) in our theological texts either. Langford, in writing about Lao refugees struggling with American hospital protocols, asks, “How do we make sense of…ghostly figures…without “anthropologizing” or “psychologizing” them, that is, without reducing them to examples of cultural belief or psychic symbols of trauma?” (Langford 2005, 43; see also Chakrabarty 2000, 105).

I, like most academics, dismissed interaction with the spirits, trees, and dreams as peripheral to the real revolutionary work of materialist theory and political theology. I argue here that scholars, activists, peace professionals of the North must develop a broader “ecology of knowledge” (Santos 2004) to learn how certain communities interact with the invisible realms and employ different contours of being and knowing: that statues call out in dreams, for example, or hungry ghosts haunt.

Ecumene in search of an advocate

There is surprisingly little work in the field of religion, conflict and peacemaking that investigates the relationship of mythic texts, phantasmic realms, and non-rational epistemologies (dreams, apparitions, omens, and signs) that offer individual healing, community guidance, and help with coexistence. Embarking on an "anthropology of the imagination,” my current work takes seriously the social imaginary of local religious communities and those who seek out the invisible world for guidance and solace. It is focuses particularly on religious dreams in “undreamy times” (Mittermaier 2010). I am currently studying the role of epiphany dreams during and after revolutionary conflict. In the cases of Our Lady of Lourdes and St. Francis, the figures appeared in the dreams of Khmer Buddhists and Roman Catholic Vietnamese settlers, communities in tension.

The field of conflict studies and various peacebuilding organizations has developed since World War II. Mennonite peacemaker John Paul Lederach’s (2005) concept of conflict transformation considers life-giving change processes to reduce violence, increase justice in social structures, and transform human relationships.[1] Lederach now plays a key role in the academic field of religion and peacebuilding which emerged in the late 1990s. There are a growing number of Global North Christian, Jewish, and Muslim colleagues focusing on interfaith dialogue, just peacemaking, theological sources of peace, faith-based diplomacy, forgiveness and reconciliation, and transitional and strategic justice. [2] But they do not refer to dreams, visions, apparitions and miraculous interventions as a part of their work. And what of religious violence? Mark Juergensmeyer (2003) is a proponent of “strong religion,” an argument for the unique nature of contemporary religious political violence and the role of “cosmic war.” In the minds of those engaged in religious conflict, these current wars are conducted simultaneously on earth and in heaven.[3] He and others writing on religious violence do not show how these religious forces also elaborate on the devils and hungry ghosts, the preta, in these cosmological worldviews. Peg Levine, in Love and Dread in Cambodia. Weddings, Births and Ritual Harm under the Khmer Rouge argues that Cambodia trauma literature and “genocide literature” rarely refer to spirits, unfinished rituals and the attendant “cosmological angst" (Levine 2010).

I have worked with resettlement of Southeast Asian refugees in the United States and a U.S. “processing center” in the Philippines from the late 1970s through 1990s and then studied post conflict reconstruction after Cambodia’s 1992 Peace Accords. From 2005 to 2010, I was a US faculty for an intensive, applied conflict transformation MA program in Phnom Penh. The Applied Conflict Transformation Studies program draws practitioners from peacebuilding programs throughout the region (Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka, India, Cambodia, Philippines). These peacebuilding programs are often faith-based INGOs such as World Vision, Mennonites, Quakers, Caritas and Catholic Relief Services with local NGOs that are Buddhist or Muslim. [4] Lederach in The Moral Imagination acknowledges the messy, inspired, and indeterminate ways conflicts often are resolved (2005). But peacebuilding NGOs are driven by donors who have pressed to show measurable results, not an easy task in the field. Because of this, NGO staff aren’t often encouraged to reflect “soft” problems of the conflict -- the cultural, psychological and religious dimensions of the social problems they are called upon to address. In many way, my quest here to to ask what it would mean for peace practitioners, not only clergy and religious adepts, to consider a multivaried ecumene.

Ecumene as an empire of exclusion

A claim to “reassemble” the oikouménē requires some attention to its genealogy. Christianity refers to the oikouménē, a Greek term, as the church and the church’s intent to bring the gospel to the whole world. The ecumenical world is made up of churches united in their difference. But the notion of the ecumene has an imperial history. On a conceptual level, it maps out the spaces we consider “inhabited.” It distinguishes between realms of the known and realm of the unknown. In this sense it foregrounds Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ notion of Abyssal thinking, which I will refer to later. Greeks divided their oikouménē as “the inhabited world” into three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa (Libya in Greek sources) (Stewart 2012, 143). Beyond these worlds were barbarian lands. When Rome colonized the Hellenized world, Romans took oikouménē to mean first “the entire Roman world,” then “the whole inhabited world,” and with it, their imperial practices (Horsley 2003, 22; Nadella 2016). In keeping with this, New Testament writers referred to the oikouménē as the imperial world fifteen times in the gospels. Joseph and Mary, for example, return to Bethlehem due to an imperial decree that “all the world” (oikouménē) be subject to census (Luke 2:1).

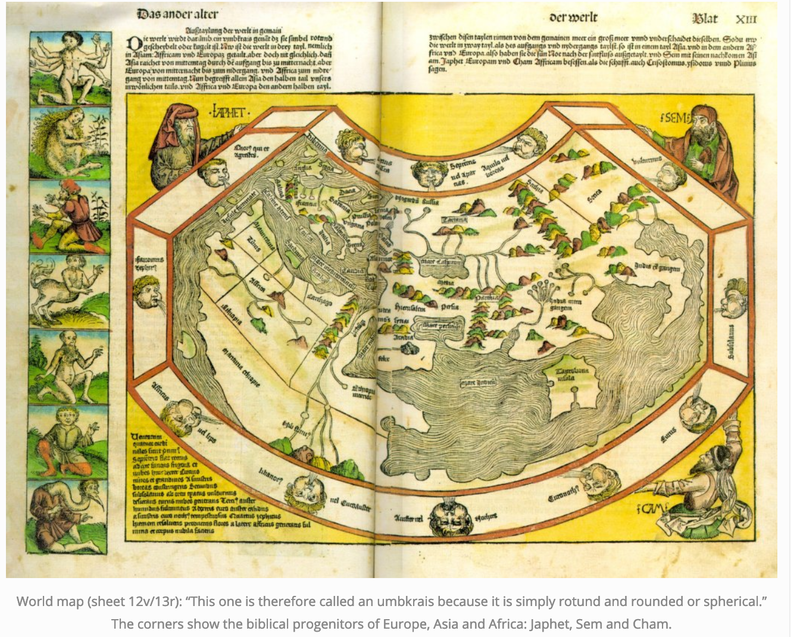

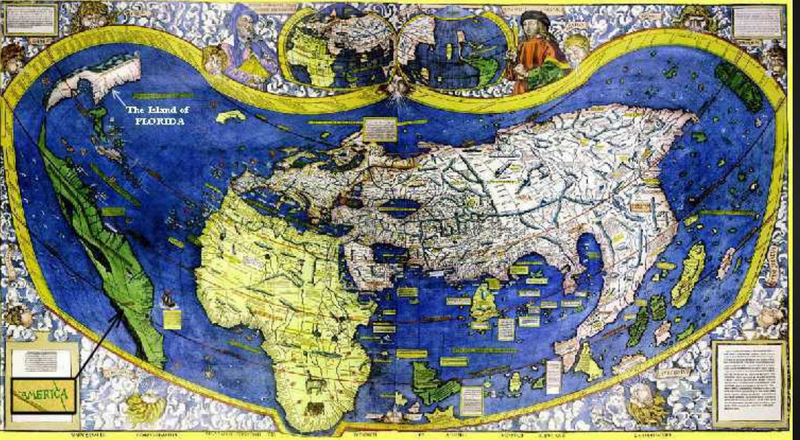

The Greek notion of ecumene as exclusion was also replicated by Rome. The "terra incognita," regions that were not mapped, were populated by fantastic and grotesque people with heads like dogs and cannibals. When Constantine Christianized the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire's maps of political territories placed Jerusalem at the center and Christ overlooking the world, attended by angels (Stewart 2012; Romm 1992). This dynamic of dominance and exclusion continued through the middle ages. Cartographers inscribed imaginary creatures of the terra incognita at the margins of the map. At the advent of modernity, one can see the “known world’s” mythology of the margin. The famous Nuremberg Chronicle (or “Book of Chronicles”) appeared in 1493 at the triumph of Catholic Spain’s Reconquista over the Moors of Andalusia. Its biblical world history shows three continents populated by Noah’s sons: Shem in Asia, Ham in Africa and Japeth in Europe. Shunted to the terra incognita are the excluded races: one-footed Sciopods, reverse-footed Antipods, bearded women, and one-eyed monsters (Friedrich 2004, 749). In 1507, a decade after the Nuremberg Chronicles, Waldseemuller’s World Map redrew the known world. One of the most important maps in the history of European cartography, it reveals a world ripe for conquest: a continent separated from Asia and a new ocean: the Pacific. Though not visually present, Incas, Mayans, and other New World “savages” replace the Sciopods at the margins.

Dussel (1993) claims that the modern ecumene came into being when Europe advanced against the Islamic world to the east and “discovered” the Americas to the west. In so doing, Europe was able to reposition itself at the very center of this newly conceived ecumene. He asserts that contemporary modernity was born when Europe, by posing against an “other,” could colonize “an alterity [otherness] that gave back its image of itself.” This “American crucible” forged our modern conceptions of ethnicity, race, gender, nation, labor, and economic development (Quijano and Wallerstein 1992). For decolonial theorists, the architecture of this “coloniality of power” is based on an epistemic falsehood, a pensiemente unico in which no alternative ways of thinking are possible, those "incognita" once again forced to the margins.

Ecumene beyond the Abyss

Portuguese decolonial theorist Boaventura de Sousa Santos argues for a “cognitive justice” that challenges this current pensiemente unico, a kind of cognitive ecumene that dominates what we claim to "know." He offers the spatial metaphor of “Abyssal thinking” as an epistemological divide dominated by Western epistemologies that pose as valid, true, rational, and normal. On the non-Western side of the divide, a newer version of the medieval terra incognita, there is no real knowledge. “There are beliefs, opinions, intuitive or subjective understandings, which, at the most, may become objects or raw materials for scientific enquiry” (Santos 2007, 80). This reality is particular and incomprehensible (Santos 2014, 120).

To engage post-Abyssal thinking, says Santos, we must embrace the anti-imperial “epistemology of the South” (2014). This is not a geographical South, but a multiplicity of epistemological souths, counter-knowledges emerging from peoples’ struggles. Taken together, they produce an “ecology of knowledge” that widens the territory of the knowable to collapse the divide between ways of knowing. De Sousa Santos concedes that preparing the conditions for a post-Abyssal thinking is a difficult, complex task. Western theory has to be deprived of its abyss(m)al characteristics, prominent among them a claim to universality and the monopoly of truth, what might call its empire of exclusion.

How do we offer a critical engagement with a post-Abyssal way of knowing, to develop an ecology of knowledge? How do we balance our incredulity, or temper the stories of others, or interrogate the inexplicable? A post-Abyssal reflection on my encounter with the preta in Phnom Penh would set it within a rich discussion in academic circles about an affirmation of the “extra-ordinary” (Goulet and Miller 2007), the “super-natural” (Strieber and Kripal 2016; cf. Kripal 2010), and indigenous ways of knowing (Tinker 2004). These scholars ask how one investigates the invisible, ghosts, rocks, or extraterrestrial creatures -- entities outside modern rationality.

This wider ecology of knowledge must include a new ontologies, new notions of the social. We return to Latour. In his controversial critique of the fundamental basis of sociology, he defines the social “not as a special domain, a specific realm, or a particular sort of thing, but only as a very peculiar movement of re-association and reassembling” (Latour 2005, 7). This reassembling refers to a radical relationality best understood by Latour and others as an assemblage. An assemblage thus clusters every “thing,” such as a statue, God, a landmine, utterances, happenings, or events as composites rather than, as is traditionally held, isolated substances (Bonta and Proveti 2004). In this sense, Latour reassembles all human action within a constellation of relation to other entities which are also attributed agency. This is very radical. Not only do humans or sentient beings have agency, but also what we've called "inanimate" entities (vinegar, guns, hammers, paper). He calls these "inanimate" entities quasi-agents or “actants” that (or who) participate in social interactions. Actants are anything that “modif[ies] other actors through a series of” actions (Latour 2004, 75). Agency is thus determined as one thing modifying another. Vital materialists and speculative realists argue that actants are garbage dumps, video games, and cyborgs. They are not objects but subjects of a flat, ontologically plural community. As political ecologist Jane Bennett argues, if they are subjects, then they are politically constituted and demand a hearing (Bennett 2010). But what does this really mean? These particular actants have agency in relation to other agents. But is there any communication between humans and other than human actants?

Dream worlds and metaphysical bodies

In this reassembled ecumene, which affirms an plurality of persons and bodies communicating within an ecology of knowledge, I have been investigating the cross-cosmological significance of statues who appear in dreams, requesting to be recovered from rivers, caves, and ricefields. The cases I offer are based on a particular kind of appearance: epiphany dreams. Epiphaneia means “manifestation” (Miller 1997). Epiphany dreams consist of the appearance to the dreamer of an authoritative personage who may be divine or represent a god, and this figure conveys instructions or information. Dreams offer an epistemological access of encounter for overlapping ontologies, where humans and spirit languages can be understood. Western psychological language refers to a dimension “within” the person, while in other cultures are attributed to an exterior realm. Dreams are considered borderlands of the visible/invisible, dead/living, awake/sleep in which figures come ”from outside.” As "porous selves" these dreamers consider their bodies available for such visitations. Integrated into the cosmos, the person with a detachable soul travels out of the body and spirits can travel into the dream.

Here is a brief overview of those stories.

I first learned about statue recovery from a Vietnamese Catholic priest at a Vietnamese immigrant fishing village along the Mekong near Wat Champa. The priest relayed how, when Wat Champa was a Khmer Rouge commune in the 1970s, an elderly Khmer man was afflicted by a recurrent dream. Each night, a “lok ta “ (old man) appeared, saying “Take me out of the river and I will help you.” Deep into the third night, the man slipped to the Mekong and found a statue stuck in the mud. He hid it. The lustral water he poured over statue healed both humans and beasts. Who was this powerful spirit? The statue’s identity was a mystery until a ragtag band of Vietnamese settlers arrived in Wat Champa and recognizing it, called out, “St Francis Xavier!” For several years, the embattled Khmer and Vietnamese communities shared admiration for the power of the saint and his statue.

In 2008, almost thirty years after the Khmer Rouge era, another Catholic statue, this time of Mary, was recovered from the waters. During the most auspicious days of the year—Khmer New Year—Buddhist Vietnamese fisher-folk pulled an encrusted, six-foot bronze statue out from the confluence of rivers that meet at the small village of Areykasat, across from Phnom Penh. When the Vietnamese fisher-folk saw what they pulled out of the river, they brought it to shore with the intention to sell it. Their Catholic Vietnamese neighbors immediately recognized the statue as Our Lady of Lourdes. The Buddhist fisher-folk set a price so steep (ten thousand riel) that their Catholic neighbors despaired. That night, in the Buddhist fisherman’s house, where Mary’s statue was kept, her spirit circled the ceiling, so frightening her host that he convinced his friends in the morning to donate their prize to the church before she cursed them. The Vietnamese Mary Queen of Peace parish built a high grotto for the statue and called her “Our Mother of the Mekong.” It was assumed that the statue had been dropped overboard by Vietnamese Catholics fleeing the violent anti-Vietnamese purges of the 1970s. Four years later, during the 2012 ASEAN meeting in Phnom Penh, another statue of Mary with the infant Jesus was recovered from the Mekong. In this case, a Buddhist Vietnamese fisherman dreamed the directive form Jesus to pick up another statue near the place in the river where the first Mary was discovered. Both statues are now at Mary Queen of Peace church and are greatly venerated, drawing weekly busloads of pilgrims from Vietnam. Questions linger about these statues and the ways they have transformed this small Catholic Vietnamese fishing village, a community at the periphery of the Khmer political body.

In 2013, I interviewed key Catholic priests associated with both Wat Champa and Areykasat, attended the large celebration Mass of the first Mary on Cambodian New Year, April 16. One week after that mass celebration, my research shifted dramatically to include two dream recoveries of Khmer statues. My colleague Samnang Seng is a well known peace activist in Cambodia who has designed and directed interfaith projects. These two Khmer incidents of dream-inspired rescues occurred within a month of each other, the first on Cambodian New Year in Stung Treng, close to the Lao border. Stung Treng was originally part of two Lao kingdoms before the French ceded it to Cambodia. A 14 year-old desperately poor settler dreamed that two monks guided him to a nearby cave to rescue statues. He found seventy-one small Buddhas high on a ledge in one of the cave’s caverns. Though he had strict orders from his dream visitors to “take the statues to the royal palace,” the statues languish in the Stung Treng Provincial museum.

Fourteen days later on tngai sel, Buddhist new moon day, a rice farmer was told in a dream to “take them out”. He went to his rice field in Banteay Meanchay, the far west of Cambodia and discovered two 12th century Bayon-era Hanuman statues with their pedestals. The dreamer and his wife were escorted to Phnom Penh by Venerable Monyreth, a high-ranking monk to deliver the statues to the Deputy Prime Minister. Since then, the family has been deeply embedded in the Hanuman myth, particularly Mr. Lim’s son and sister-in-law, who have themselves become conduits for transmitting Hanuman’s wishes to the Cambodian people. Mr. Seng and I visited Stung Treng and Banteay Meanchay since the initial meetings and Mr. Seng has returned to both sites to meet with family and government officials.

These five incidents of statue-rescue share several attributes. They occurred through dreams on auspicious days. The dreamer was not a religious specialist but a poor member of a marginal community. The dream recovery affected the dreamer, their family and community, affixing them to the mythic narrative of a statue rescue. That these statues are Catholic, Buddhist and Hindu, and the dreamers Khmer and Vietnamese offers an intriguing oneiric ecumene (cf Hannerz 1989) of cosmological détente, an assemblage of human, statue, and environmental actants.

Conclusion

This is an admittedly brief conclusion for so dense an argument. The ecumenes we have traveled have been the production of Eurocentric modernity, which has obscured other knowledges, peoples, and realities from our “whole inhabited earth.” This is particularly problematic for marginal communities in conflict zones who rely on "invisible aid" but also experience spectral trauma when their cosmos is torn apart. I have considered how Cambodia’s conflict zone in its post-conflict setting offers a critical decolonial challenge to that modernity.

If we consider this version of a reassembled ecumene, we are offered a radically different way to experience and interpret the world, one in which simultaneous other worlds coexist with the quotidian world we occupy. We are left with many questions. What is a post-Abyssal approach to those whose encounters with metaphysical worlds are rich and uninterrogated? Since the interpretation of dreams is such a long historic and varied practice across cultures, what criteria might we use to evaluate the veracity of a multi-faith epistemology? How do we “discern” the spirits in this pluriversal ecumene? If we take as a form of real the intervention of spirits through their statues into our hybrid ecumene, how do we continue to interpret the statues as actants? How do we as scholars interact and interpret such a ecumene reassembled?

*********************************************************************

*Adapted from Kathryn Poethig, "Reassembling the Oikoimene," Mission in Context, Vol 5, Theology in the Time of Empire Series, Edited by Jione Havea, Boston: Lexington / Fortress Academics, 2020

[1] John Paul Lederach, The Little Book of Conflict Transformation. (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2003). He distinguishes it from conflict resolution which is based on a negative assessment of conflicts which must be ended, inferring that they can actually be resolved in short-term interventions. He also critiques conflict management, which while understanding conflicts entrenched processes, assumes that communities can be controlled and that the purpose of this management is to take care of the conflict, not root problems.

[2] Raymond Hemlick and Rodney Peterson. Eds. Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Religion, Public Policy, & Conflict Transformation (Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press, 2002); In the United States, the key religion and peacemaking graduate programs include University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, Eastern Mennonite University’s Peace Studies program, Fuller School of Theology, and Emory University’s Religion, Conflict and Peacebuilding. New initiatives include the Alliance for Peacebuilding’s partnership with CDA Collaborative Learning and Search for Common Ground to convene leading global experts to develop better measure the effectiveness of inter- and intra-religious action for peacebuilding.

[3] Key works include Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999); Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Nonviolence and Peace Building in Islam: Theory and Practice (Gainsville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003); Marc Gopin, Between Eden and Armageddon: The Future of World Religion, Violence, and Peacebuilding (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Douglas Johnston, Ed. Faith-based Diplomacy: Trumping Realpolitik (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003: and Daniel Philpott, Ed. The Politics of Past Evil: Religion, Reconciliation; The Dilemmas of Transitional Justice, (Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006); David Smock Ed. Interfaith Dialogue and Peacebuilding (Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace, 2002); Glenn Stassen, Just Peacemaking: The New Paradigm for the Ethics of Peace and War (Pilgrim Press, 2008); Miroslav Volf, Exclusion & Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Abingdon Press, 1996), David R. Smock, Religious Contributions to Peacemaking: When Religion Brings Peace, Not War, PeaceWorks, no. 55, ed. David R. Smock (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2006).

[4] There are several ways that ecumenical peacebuilding has developed in Southeast Asia. There is the CCA School for Peace, now in Cambodia, and the Philippine-founded People’s Forum on Peace for Life, of which I have been a long-term member. Peace and development “regimes” develop differently in each country of conflict, which includes an amalgam of government entities, military, academic programs, institutes, multilateral funders, a range of civil society organizations which include religious organizations, and international NGOs. I am most familiar with these in the Philippines through the CPP-NPA and post-conflict Cambodia.

Works cited

Bar, Shaul. 2001. A Letter that Has Not been Read: Dreams in the Hebrew Bible. Translated by Lenn Shramm. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union Press.

Batalha, Eduardo and Viveiros de Castro. 2004. “Perspectival anthropology and the method of controlled equivocation.” Tipitií: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2(1):3–22

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bertrand, Didier. 2001. “The Names and Identities of the ‘Boramey’ Spirits Possessing Cambodian Mediums.” Asian Folklore Studies 60: 31-47.

Bird, Deborah Rose. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Bird, Deborah Rose. 2007. “Recursive Epistemologies and an Ethics of Attention.” In Extraordinary Anthropology: Transformations in the Field, edited by Jean-Guy Goulet and Granville Miller, 87-98. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bonta, Mark and John Protevi. 2004. Deleuze and Geophilosophy: A Guide and Glossary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Brownstein, Daniel. 2013. “Maps, Mapping, Globalism: Imaging the Ecumene’s Expanse,” Musing on Maps, March 8, 2013, https://dabrownstein.com/2013/03/08/maps-mapping-globalization/

Bulkeley, Kelly. 1994. The Wilderness of Dreams: Exploring the Religious Meanings of Dreams In Modern Western Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Chandler, David. 2007. A History of Cambodia. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Columbia or America: 500 years of Controversy. First Maps of the New World. Cornel University, (accessed December 12, 2016) https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/columbia-or-america/maps First Maps of the New World. Columbia or America: 500 years of Controversy. Cornel University https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/columbia-or-america/maps

Dussel, Enrique 1993. “Eurocentrism and Modernity (Introduction to the Frankfurt Lectures).” Boundary 2 20.3 (1993): 65-76

Friedrich, Karin. 2004. Review of Chronicle of the World: The Complete and Annotated Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, by Hartmann Schedel. The Slavonic and East European Review 82: 749-750.

Gordon, Avery. 2008 Ghostly matters: haunting and the sociological imagination. Mpls, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008

Goulet, Jean-Guy and Granville Miller, eds. 2007. Extraordinary Anthropology: Transformations in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hang, Chan Sophea, Stec Gamlan and Yay Deb. 2004. “Worshipping Kings and Queens in Cambodia Today.” In History, Buddhism, And New Religious Movements In Cambodia, edited by John Marston and Elizabeth Guthrie, 113-126. Oahu: University of Hawaii Press.

Hollywood, Amy. 2016. Acute Melancholia and Other Essays. Mysticism, History, and the Study of Religion. New York: Colombia University Press.

Horsley, Richard A. 2003. Jesus and Empire: The Kingdom of God and the New World Disorder. Grand Rapids: Fortress.

Kripal. Jeffrey J. 2010. Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kwon, Heonik. 2008. Ghosts of War in Vietnam. New York: Cambridge University Press. Langford, Jean. 2005. “Spirits of Dissent: Southeast Asian Memories and Disciplines of Death,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 25: 161-176

Latour, Bruno. 2004. “Which Cosmos, Whose Cosmopolitics? Comments on the Peace Terms of Ulrich Beck.” Common Knowledge 10:450-462 Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature. How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. Lederach, John Paul. The Moral Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Levine, Peg. 2010. Love and Dread in Cambodia. Weddings, Births and Ritual Harm under the Khmer Rouge. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Mignolo, Walter. 2011. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (ssha_transmodernity_11807. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/62j3w283).

Miller, Patricia Cox. 1997. Dreams in Late Antiquity: Studies in the Imagination of a Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nadella, Raj. 2016. “The Two Banquets: Mark’s Vision of Anti-Imperial Economics,” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 70:172–183. Orsi, Robert. 2008. “Abundant histories: Marian apparitions as alternative modernity.” Historically Speaking 9: 12–16.

Poethig, Kathryn. 2001. “Visa Trouble: Cambodian American Christians and Their Defense of Multiple Citizenships.” Religions/Globalizations: Theories and Cases edited by Dwight N. Hopkins Lois Ann Lorentzen, Eduardo Mendieta, David Batstone, 187-202. Atlanta, GA: Duke University Press.

Quijano, Anibal and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1992. “Americanity as a concept. Or The Americas in the Modern World-System.” International Journal of Social Sciences 134: 549-552.

Romm, James S. 1992. The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa . 2007. “Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges.” Revista Critica de Ciencias Sociais (http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2007-06-29-santosen.html)

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa . 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Skafish, Peter and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. 2016. “The Metaphysics of Extra-Moderns: On the Decolonization of Thought—A Conversation with Eduardo Viveiros de Castro” Common Knowledge 22: 393-414 .

Stewart, Eric C. 2012. “Reader’s Guide: New Testament Space/Spaciality.” Biblical Theology Bulletin 42: 139–50. Strieber, Whitley and Jeffrey J. Kripal. 2016. The Super Natural: A New Vision of the Unexplained. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tinker, George "Tink", "The Stones Shall Cry Out: Consciousness, Rocks and Indians," Wicazo Sa Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, Colonization/Decolonization, I (Autumn, 2004), pp. 105- 125

Latour (2005) has pressed us to "reassemble the social," to rethink what we mean by this over-used term. I ask, how can we “reassemble our ecumenes” to be more elastic with the boundaries of our real, to learn different ways of being, so that the worldviews of those we study, advocate for -- and resist --are constitutive of a range of personhoods? I will suggest that we must account for other bodies: bodies of what we might call entities or actants. Some are gendered, but in multiple ways – asexual, dimorphic, hermaphrodite – some are not. Some are invisible, spectral, some appallingly visual, others are inorganic. Some entities occupy other bodies; some are aggregates of other entities. I am interested in whether, or how, these bodies do what we humans call knowing and acting, but in different ways. This has methodological implications, and I focus here on Cambodia's spectral other-than-human world.

In refugee camps, living rooms, and among friends, I’d heard personal refugee accounts of those who had endured Cambodia’s “travesty of history” from 1975-1979 when the Khmer Rouge walked into the capital Phnom Penh and declared “Year Zero, “ inaugurating a revolutionary communist regime in which a quarter of the population was exterminated or died of malnutrition. While all cities were evacuated, the most stunning was Phnom Penh, where members of the former regime were assassinated or sent to interrogation centers such as Toul Sleng. Choeung Eck, a field of mass graves outside of town, is the most notorious of the hundreds of “killing fields.” The regime ended in early 1979 when newly socialist Vietnamese invaded, occupying Cambodia for a decade until the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1991.

This political world -- saturated with violence -- is set within a Cambodian Theravada worldview. Interaction with supernatural creatures: boramay, neak ta, and preta, is integral to Cambodian cosmology. Boramey (or parami) are spirits associated with Buddhism and manifest benevolent supernatural power. Boramey can be the attribute of a statue, such as the Leper King (Hang, Gamlan and Deb 2004) or a manifestation of mytho-historic figures such as generals or kings who possess a medium (Bertrand 2001). The boramey often speak through dreams. Neak ta, on the other hand, are guardians of the land. Friends noted that during the Khmer Rouge era, neak ta were disrupted and the palm trees would not bear fruit. Preta, hungry ghosts, inhabited desecrated holy spaces such as Buddhist wats used for storage and torture (Chandler 2007). The “killing fields” were saturated with phantasmic terror, populated with roaming preta because the near-dead had been violated, and when dead, were not properly buried (Levine 2010). They could not continue on to the next life.

Are these creatures locked into Cambodian worldviews? Do they slip out of their "representation” and visit others? I had encounters with preta and boramey in my time with Cambodians both in Asia and the United States. My spooky meet-up with a preta occurred on a travel seminar to Phnom Penh coordinated through San Francisco Theological Seminary in 1992. A decade after the Khmer Rouge departure, the city still seemed bedraggled and slightly surreal, residents four-to-a-bicycle plying Monivong Avenue, dark nights interrupted by generator-driven pools of light. Bats hung like overripe fruit in the naked trees near the UN Transitional Authority compound. Even the most prominent wats were derelict and forlorn, decapitated heads of the Buddha laid out near their stupas. So it was not entirely surprising that after a visit to Choeung Ek, my American roommate looked wan. She sat at the corner of her bed and shot me a nervous glance, “When you lie down, do you see anything?” When I said no, she hesitated, “When I lie down, I see three men with machine guns at the foot of my bed.” Chills shot up my back. The room suddenly felt ominous and cold. We improvised an exorcism, and when we ran out of ideas, we went to sleep. I was startled awake by the pressure of a ghostly body on top of me. I plopped a pillow over my head, praying feverishly, until—whoosh—the room felt clear. “A preta,” mused a Cambodian friend when I relayed the story later. There seemed to be many preta prowling around Phnom Penh.

Ghosts, neak ta, devata as inhabitants of our worlds, are social actors often denied a voice in the stories we tell about war, survival, and post conflict, even though they are everywhere. In theological work on conflict, I don’t often hear about prophetic dreams and signs that help survivors map catastrophic events, or statues, amulets or tatoos that protect border crossings, or apparitions of Mary or Kwan Yin who appear to Vietnamese boat people when their engines stall or pirates trail them. What do we do with Jesus appearing to a Buddhist prisoner of the Khmer Rouge with advice that saves him? Family stories like these disappear from the “refugee narrative” upon arrival in the United States, and they are not (often) in our theological texts either. Langford, in writing about Lao refugees struggling with American hospital protocols, asks, “How do we make sense of…ghostly figures…without “anthropologizing” or “psychologizing” them, that is, without reducing them to examples of cultural belief or psychic symbols of trauma?” (Langford 2005, 43; see also Chakrabarty 2000, 105).

I, like most academics, dismissed interaction with the spirits, trees, and dreams as peripheral to the real revolutionary work of materialist theory and political theology. I argue here that scholars, activists, peace professionals of the North must develop a broader “ecology of knowledge” (Santos 2004) to learn how certain communities interact with the invisible realms and employ different contours of being and knowing: that statues call out in dreams, for example, or hungry ghosts haunt.

Ecumene in search of an advocate

There is surprisingly little work in the field of religion, conflict and peacemaking that investigates the relationship of mythic texts, phantasmic realms, and non-rational epistemologies (dreams, apparitions, omens, and signs) that offer individual healing, community guidance, and help with coexistence. Embarking on an "anthropology of the imagination,” my current work takes seriously the social imaginary of local religious communities and those who seek out the invisible world for guidance and solace. It is focuses particularly on religious dreams in “undreamy times” (Mittermaier 2010). I am currently studying the role of epiphany dreams during and after revolutionary conflict. In the cases of Our Lady of Lourdes and St. Francis, the figures appeared in the dreams of Khmer Buddhists and Roman Catholic Vietnamese settlers, communities in tension.

The field of conflict studies and various peacebuilding organizations has developed since World War II. Mennonite peacemaker John Paul Lederach’s (2005) concept of conflict transformation considers life-giving change processes to reduce violence, increase justice in social structures, and transform human relationships.[1] Lederach now plays a key role in the academic field of religion and peacebuilding which emerged in the late 1990s. There are a growing number of Global North Christian, Jewish, and Muslim colleagues focusing on interfaith dialogue, just peacemaking, theological sources of peace, faith-based diplomacy, forgiveness and reconciliation, and transitional and strategic justice. [2] But they do not refer to dreams, visions, apparitions and miraculous interventions as a part of their work. And what of religious violence? Mark Juergensmeyer (2003) is a proponent of “strong religion,” an argument for the unique nature of contemporary religious political violence and the role of “cosmic war.” In the minds of those engaged in religious conflict, these current wars are conducted simultaneously on earth and in heaven.[3] He and others writing on religious violence do not show how these religious forces also elaborate on the devils and hungry ghosts, the preta, in these cosmological worldviews. Peg Levine, in Love and Dread in Cambodia. Weddings, Births and Ritual Harm under the Khmer Rouge argues that Cambodia trauma literature and “genocide literature” rarely refer to spirits, unfinished rituals and the attendant “cosmological angst" (Levine 2010).

I have worked with resettlement of Southeast Asian refugees in the United States and a U.S. “processing center” in the Philippines from the late 1970s through 1990s and then studied post conflict reconstruction after Cambodia’s 1992 Peace Accords. From 2005 to 2010, I was a US faculty for an intensive, applied conflict transformation MA program in Phnom Penh. The Applied Conflict Transformation Studies program draws practitioners from peacebuilding programs throughout the region (Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka, India, Cambodia, Philippines). These peacebuilding programs are often faith-based INGOs such as World Vision, Mennonites, Quakers, Caritas and Catholic Relief Services with local NGOs that are Buddhist or Muslim. [4] Lederach in The Moral Imagination acknowledges the messy, inspired, and indeterminate ways conflicts often are resolved (2005). But peacebuilding NGOs are driven by donors who have pressed to show measurable results, not an easy task in the field. Because of this, NGO staff aren’t often encouraged to reflect “soft” problems of the conflict -- the cultural, psychological and religious dimensions of the social problems they are called upon to address. In many way, my quest here to to ask what it would mean for peace practitioners, not only clergy and religious adepts, to consider a multivaried ecumene.

Ecumene as an empire of exclusion

A claim to “reassemble” the oikouménē requires some attention to its genealogy. Christianity refers to the oikouménē, a Greek term, as the church and the church’s intent to bring the gospel to the whole world. The ecumenical world is made up of churches united in their difference. But the notion of the ecumene has an imperial history. On a conceptual level, it maps out the spaces we consider “inhabited.” It distinguishes between realms of the known and realm of the unknown. In this sense it foregrounds Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ notion of Abyssal thinking, which I will refer to later. Greeks divided their oikouménē as “the inhabited world” into three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa (Libya in Greek sources) (Stewart 2012, 143). Beyond these worlds were barbarian lands. When Rome colonized the Hellenized world, Romans took oikouménē to mean first “the entire Roman world,” then “the whole inhabited world,” and with it, their imperial practices (Horsley 2003, 22; Nadella 2016). In keeping with this, New Testament writers referred to the oikouménē as the imperial world fifteen times in the gospels. Joseph and Mary, for example, return to Bethlehem due to an imperial decree that “all the world” (oikouménē) be subject to census (Luke 2:1).

The Greek notion of ecumene as exclusion was also replicated by Rome. The "terra incognita," regions that were not mapped, were populated by fantastic and grotesque people with heads like dogs and cannibals. When Constantine Christianized the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire's maps of political territories placed Jerusalem at the center and Christ overlooking the world, attended by angels (Stewart 2012; Romm 1992). This dynamic of dominance and exclusion continued through the middle ages. Cartographers inscribed imaginary creatures of the terra incognita at the margins of the map. At the advent of modernity, one can see the “known world’s” mythology of the margin. The famous Nuremberg Chronicle (or “Book of Chronicles”) appeared in 1493 at the triumph of Catholic Spain’s Reconquista over the Moors of Andalusia. Its biblical world history shows three continents populated by Noah’s sons: Shem in Asia, Ham in Africa and Japeth in Europe. Shunted to the terra incognita are the excluded races: one-footed Sciopods, reverse-footed Antipods, bearded women, and one-eyed monsters (Friedrich 2004, 749). In 1507, a decade after the Nuremberg Chronicles, Waldseemuller’s World Map redrew the known world. One of the most important maps in the history of European cartography, it reveals a world ripe for conquest: a continent separated from Asia and a new ocean: the Pacific. Though not visually present, Incas, Mayans, and other New World “savages” replace the Sciopods at the margins.

Dussel (1993) claims that the modern ecumene came into being when Europe advanced against the Islamic world to the east and “discovered” the Americas to the west. In so doing, Europe was able to reposition itself at the very center of this newly conceived ecumene. He asserts that contemporary modernity was born when Europe, by posing against an “other,” could colonize “an alterity [otherness] that gave back its image of itself.” This “American crucible” forged our modern conceptions of ethnicity, race, gender, nation, labor, and economic development (Quijano and Wallerstein 1992). For decolonial theorists, the architecture of this “coloniality of power” is based on an epistemic falsehood, a pensiemente unico in which no alternative ways of thinking are possible, those "incognita" once again forced to the margins.

Ecumene beyond the Abyss

Portuguese decolonial theorist Boaventura de Sousa Santos argues for a “cognitive justice” that challenges this current pensiemente unico, a kind of cognitive ecumene that dominates what we claim to "know." He offers the spatial metaphor of “Abyssal thinking” as an epistemological divide dominated by Western epistemologies that pose as valid, true, rational, and normal. On the non-Western side of the divide, a newer version of the medieval terra incognita, there is no real knowledge. “There are beliefs, opinions, intuitive or subjective understandings, which, at the most, may become objects or raw materials for scientific enquiry” (Santos 2007, 80). This reality is particular and incomprehensible (Santos 2014, 120).

To engage post-Abyssal thinking, says Santos, we must embrace the anti-imperial “epistemology of the South” (2014). This is not a geographical South, but a multiplicity of epistemological souths, counter-knowledges emerging from peoples’ struggles. Taken together, they produce an “ecology of knowledge” that widens the territory of the knowable to collapse the divide between ways of knowing. De Sousa Santos concedes that preparing the conditions for a post-Abyssal thinking is a difficult, complex task. Western theory has to be deprived of its abyss(m)al characteristics, prominent among them a claim to universality and the monopoly of truth, what might call its empire of exclusion.

How do we offer a critical engagement with a post-Abyssal way of knowing, to develop an ecology of knowledge? How do we balance our incredulity, or temper the stories of others, or interrogate the inexplicable? A post-Abyssal reflection on my encounter with the preta in Phnom Penh would set it within a rich discussion in academic circles about an affirmation of the “extra-ordinary” (Goulet and Miller 2007), the “super-natural” (Strieber and Kripal 2016; cf. Kripal 2010), and indigenous ways of knowing (Tinker 2004). These scholars ask how one investigates the invisible, ghosts, rocks, or extraterrestrial creatures -- entities outside modern rationality.

This wider ecology of knowledge must include a new ontologies, new notions of the social. We return to Latour. In his controversial critique of the fundamental basis of sociology, he defines the social “not as a special domain, a specific realm, or a particular sort of thing, but only as a very peculiar movement of re-association and reassembling” (Latour 2005, 7). This reassembling refers to a radical relationality best understood by Latour and others as an assemblage. An assemblage thus clusters every “thing,” such as a statue, God, a landmine, utterances, happenings, or events as composites rather than, as is traditionally held, isolated substances (Bonta and Proveti 2004). In this sense, Latour reassembles all human action within a constellation of relation to other entities which are also attributed agency. This is very radical. Not only do humans or sentient beings have agency, but also what we've called "inanimate" entities (vinegar, guns, hammers, paper). He calls these "inanimate" entities quasi-agents or “actants” that (or who) participate in social interactions. Actants are anything that “modif[ies] other actors through a series of” actions (Latour 2004, 75). Agency is thus determined as one thing modifying another. Vital materialists and speculative realists argue that actants are garbage dumps, video games, and cyborgs. They are not objects but subjects of a flat, ontologically plural community. As political ecologist Jane Bennett argues, if they are subjects, then they are politically constituted and demand a hearing (Bennett 2010). But what does this really mean? These particular actants have agency in relation to other agents. But is there any communication between humans and other than human actants?

Dream worlds and metaphysical bodies

In this reassembled ecumene, which affirms an plurality of persons and bodies communicating within an ecology of knowledge, I have been investigating the cross-cosmological significance of statues who appear in dreams, requesting to be recovered from rivers, caves, and ricefields. The cases I offer are based on a particular kind of appearance: epiphany dreams. Epiphaneia means “manifestation” (Miller 1997). Epiphany dreams consist of the appearance to the dreamer of an authoritative personage who may be divine or represent a god, and this figure conveys instructions or information. Dreams offer an epistemological access of encounter for overlapping ontologies, where humans and spirit languages can be understood. Western psychological language refers to a dimension “within” the person, while in other cultures are attributed to an exterior realm. Dreams are considered borderlands of the visible/invisible, dead/living, awake/sleep in which figures come ”from outside.” As "porous selves" these dreamers consider their bodies available for such visitations. Integrated into the cosmos, the person with a detachable soul travels out of the body and spirits can travel into the dream.

Here is a brief overview of those stories.

I first learned about statue recovery from a Vietnamese Catholic priest at a Vietnamese immigrant fishing village along the Mekong near Wat Champa. The priest relayed how, when Wat Champa was a Khmer Rouge commune in the 1970s, an elderly Khmer man was afflicted by a recurrent dream. Each night, a “lok ta “ (old man) appeared, saying “Take me out of the river and I will help you.” Deep into the third night, the man slipped to the Mekong and found a statue stuck in the mud. He hid it. The lustral water he poured over statue healed both humans and beasts. Who was this powerful spirit? The statue’s identity was a mystery until a ragtag band of Vietnamese settlers arrived in Wat Champa and recognizing it, called out, “St Francis Xavier!” For several years, the embattled Khmer and Vietnamese communities shared admiration for the power of the saint and his statue.

In 2008, almost thirty years after the Khmer Rouge era, another Catholic statue, this time of Mary, was recovered from the waters. During the most auspicious days of the year—Khmer New Year—Buddhist Vietnamese fisher-folk pulled an encrusted, six-foot bronze statue out from the confluence of rivers that meet at the small village of Areykasat, across from Phnom Penh. When the Vietnamese fisher-folk saw what they pulled out of the river, they brought it to shore with the intention to sell it. Their Catholic Vietnamese neighbors immediately recognized the statue as Our Lady of Lourdes. The Buddhist fisher-folk set a price so steep (ten thousand riel) that their Catholic neighbors despaired. That night, in the Buddhist fisherman’s house, where Mary’s statue was kept, her spirit circled the ceiling, so frightening her host that he convinced his friends in the morning to donate their prize to the church before she cursed them. The Vietnamese Mary Queen of Peace parish built a high grotto for the statue and called her “Our Mother of the Mekong.” It was assumed that the statue had been dropped overboard by Vietnamese Catholics fleeing the violent anti-Vietnamese purges of the 1970s. Four years later, during the 2012 ASEAN meeting in Phnom Penh, another statue of Mary with the infant Jesus was recovered from the Mekong. In this case, a Buddhist Vietnamese fisherman dreamed the directive form Jesus to pick up another statue near the place in the river where the first Mary was discovered. Both statues are now at Mary Queen of Peace church and are greatly venerated, drawing weekly busloads of pilgrims from Vietnam. Questions linger about these statues and the ways they have transformed this small Catholic Vietnamese fishing village, a community at the periphery of the Khmer political body.

In 2013, I interviewed key Catholic priests associated with both Wat Champa and Areykasat, attended the large celebration Mass of the first Mary on Cambodian New Year, April 16. One week after that mass celebration, my research shifted dramatically to include two dream recoveries of Khmer statues. My colleague Samnang Seng is a well known peace activist in Cambodia who has designed and directed interfaith projects. These two Khmer incidents of dream-inspired rescues occurred within a month of each other, the first on Cambodian New Year in Stung Treng, close to the Lao border. Stung Treng was originally part of two Lao kingdoms before the French ceded it to Cambodia. A 14 year-old desperately poor settler dreamed that two monks guided him to a nearby cave to rescue statues. He found seventy-one small Buddhas high on a ledge in one of the cave’s caverns. Though he had strict orders from his dream visitors to “take the statues to the royal palace,” the statues languish in the Stung Treng Provincial museum.

Fourteen days later on tngai sel, Buddhist new moon day, a rice farmer was told in a dream to “take them out”. He went to his rice field in Banteay Meanchay, the far west of Cambodia and discovered two 12th century Bayon-era Hanuman statues with their pedestals. The dreamer and his wife were escorted to Phnom Penh by Venerable Monyreth, a high-ranking monk to deliver the statues to the Deputy Prime Minister. Since then, the family has been deeply embedded in the Hanuman myth, particularly Mr. Lim’s son and sister-in-law, who have themselves become conduits for transmitting Hanuman’s wishes to the Cambodian people. Mr. Seng and I visited Stung Treng and Banteay Meanchay since the initial meetings and Mr. Seng has returned to both sites to meet with family and government officials.

These five incidents of statue-rescue share several attributes. They occurred through dreams on auspicious days. The dreamer was not a religious specialist but a poor member of a marginal community. The dream recovery affected the dreamer, their family and community, affixing them to the mythic narrative of a statue rescue. That these statues are Catholic, Buddhist and Hindu, and the dreamers Khmer and Vietnamese offers an intriguing oneiric ecumene (cf Hannerz 1989) of cosmological détente, an assemblage of human, statue, and environmental actants.

Conclusion

This is an admittedly brief conclusion for so dense an argument. The ecumenes we have traveled have been the production of Eurocentric modernity, which has obscured other knowledges, peoples, and realities from our “whole inhabited earth.” This is particularly problematic for marginal communities in conflict zones who rely on "invisible aid" but also experience spectral trauma when their cosmos is torn apart. I have considered how Cambodia’s conflict zone in its post-conflict setting offers a critical decolonial challenge to that modernity.

If we consider this version of a reassembled ecumene, we are offered a radically different way to experience and interpret the world, one in which simultaneous other worlds coexist with the quotidian world we occupy. We are left with many questions. What is a post-Abyssal approach to those whose encounters with metaphysical worlds are rich and uninterrogated? Since the interpretation of dreams is such a long historic and varied practice across cultures, what criteria might we use to evaluate the veracity of a multi-faith epistemology? How do we “discern” the spirits in this pluriversal ecumene? If we take as a form of real the intervention of spirits through their statues into our hybrid ecumene, how do we continue to interpret the statues as actants? How do we as scholars interact and interpret such a ecumene reassembled?

*********************************************************************

*Adapted from Kathryn Poethig, "Reassembling the Oikoimene," Mission in Context, Vol 5, Theology in the Time of Empire Series, Edited by Jione Havea, Boston: Lexington / Fortress Academics, 2020

[1] John Paul Lederach, The Little Book of Conflict Transformation. (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2003). He distinguishes it from conflict resolution which is based on a negative assessment of conflicts which must be ended, inferring that they can actually be resolved in short-term interventions. He also critiques conflict management, which while understanding conflicts entrenched processes, assumes that communities can be controlled and that the purpose of this management is to take care of the conflict, not root problems.

[2] Raymond Hemlick and Rodney Peterson. Eds. Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Religion, Public Policy, & Conflict Transformation (Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press, 2002); In the United States, the key religion and peacemaking graduate programs include University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, Eastern Mennonite University’s Peace Studies program, Fuller School of Theology, and Emory University’s Religion, Conflict and Peacebuilding. New initiatives include the Alliance for Peacebuilding’s partnership with CDA Collaborative Learning and Search for Common Ground to convene leading global experts to develop better measure the effectiveness of inter- and intra-religious action for peacebuilding.

[3] Key works include Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999); Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Nonviolence and Peace Building in Islam: Theory and Practice (Gainsville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003); Marc Gopin, Between Eden and Armageddon: The Future of World Religion, Violence, and Peacebuilding (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Douglas Johnston, Ed. Faith-based Diplomacy: Trumping Realpolitik (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003: and Daniel Philpott, Ed. The Politics of Past Evil: Religion, Reconciliation; The Dilemmas of Transitional Justice, (Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006); David Smock Ed. Interfaith Dialogue and Peacebuilding (Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace, 2002); Glenn Stassen, Just Peacemaking: The New Paradigm for the Ethics of Peace and War (Pilgrim Press, 2008); Miroslav Volf, Exclusion & Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Abingdon Press, 1996), David R. Smock, Religious Contributions to Peacemaking: When Religion Brings Peace, Not War, PeaceWorks, no. 55, ed. David R. Smock (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2006).

[4] There are several ways that ecumenical peacebuilding has developed in Southeast Asia. There is the CCA School for Peace, now in Cambodia, and the Philippine-founded People’s Forum on Peace for Life, of which I have been a long-term member. Peace and development “regimes” develop differently in each country of conflict, which includes an amalgam of government entities, military, academic programs, institutes, multilateral funders, a range of civil society organizations which include religious organizations, and international NGOs. I am most familiar with these in the Philippines through the CPP-NPA and post-conflict Cambodia.

Works cited

Bar, Shaul. 2001. A Letter that Has Not been Read: Dreams in the Hebrew Bible. Translated by Lenn Shramm. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union Press.

Batalha, Eduardo and Viveiros de Castro. 2004. “Perspectival anthropology and the method of controlled equivocation.” Tipitií: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2(1):3–22

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bertrand, Didier. 2001. “The Names and Identities of the ‘Boramey’ Spirits Possessing Cambodian Mediums.” Asian Folklore Studies 60: 31-47.

Bird, Deborah Rose. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Bird, Deborah Rose. 2007. “Recursive Epistemologies and an Ethics of Attention.” In Extraordinary Anthropology: Transformations in the Field, edited by Jean-Guy Goulet and Granville Miller, 87-98. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Bonta, Mark and John Protevi. 2004. Deleuze and Geophilosophy: A Guide and Glossary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Brownstein, Daniel. 2013. “Maps, Mapping, Globalism: Imaging the Ecumene’s Expanse,” Musing on Maps, March 8, 2013, https://dabrownstein.com/2013/03/08/maps-mapping-globalization/

Bulkeley, Kelly. 1994. The Wilderness of Dreams: Exploring the Religious Meanings of Dreams In Modern Western Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Chandler, David. 2007. A History of Cambodia. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Columbia or America: 500 years of Controversy. First Maps of the New World. Cornel University, (accessed December 12, 2016) https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/columbia-or-america/maps First Maps of the New World. Columbia or America: 500 years of Controversy. Cornel University https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/columbia-or-america/maps

Dussel, Enrique 1993. “Eurocentrism and Modernity (Introduction to the Frankfurt Lectures).” Boundary 2 20.3 (1993): 65-76

Friedrich, Karin. 2004. Review of Chronicle of the World: The Complete and Annotated Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, by Hartmann Schedel. The Slavonic and East European Review 82: 749-750.

Gordon, Avery. 2008 Ghostly matters: haunting and the sociological imagination. Mpls, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008

Goulet, Jean-Guy and Granville Miller, eds. 2007. Extraordinary Anthropology: Transformations in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hang, Chan Sophea, Stec Gamlan and Yay Deb. 2004. “Worshipping Kings and Queens in Cambodia Today.” In History, Buddhism, And New Religious Movements In Cambodia, edited by John Marston and Elizabeth Guthrie, 113-126. Oahu: University of Hawaii Press.

Hollywood, Amy. 2016. Acute Melancholia and Other Essays. Mysticism, History, and the Study of Religion. New York: Colombia University Press.

Horsley, Richard A. 2003. Jesus and Empire: The Kingdom of God and the New World Disorder. Grand Rapids: Fortress.

Kripal. Jeffrey J. 2010. Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kwon, Heonik. 2008. Ghosts of War in Vietnam. New York: Cambridge University Press. Langford, Jean. 2005. “Spirits of Dissent: Southeast Asian Memories and Disciplines of Death,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 25: 161-176

Latour, Bruno. 2004. “Which Cosmos, Whose Cosmopolitics? Comments on the Peace Terms of Ulrich Beck.” Common Knowledge 10:450-462 Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature. How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. Lederach, John Paul. The Moral Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Levine, Peg. 2010. Love and Dread in Cambodia. Weddings, Births and Ritual Harm under the Khmer Rouge. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Mignolo, Walter. 2011. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (ssha_transmodernity_11807. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/62j3w283).

Miller, Patricia Cox. 1997. Dreams in Late Antiquity: Studies in the Imagination of a Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nadella, Raj. 2016. “The Two Banquets: Mark’s Vision of Anti-Imperial Economics,” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 70:172–183. Orsi, Robert. 2008. “Abundant histories: Marian apparitions as alternative modernity.” Historically Speaking 9: 12–16.

Poethig, Kathryn. 2001. “Visa Trouble: Cambodian American Christians and Their Defense of Multiple Citizenships.” Religions/Globalizations: Theories and Cases edited by Dwight N. Hopkins Lois Ann Lorentzen, Eduardo Mendieta, David Batstone, 187-202. Atlanta, GA: Duke University Press.

Quijano, Anibal and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1992. “Americanity as a concept. Or The Americas in the Modern World-System.” International Journal of Social Sciences 134: 549-552.

Romm, James S. 1992. The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa . 2007. “Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges.” Revista Critica de Ciencias Sociais (http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2007-06-29-santosen.html)

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa . 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Skafish, Peter and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. 2016. “The Metaphysics of Extra-Moderns: On the Decolonization of Thought—A Conversation with Eduardo Viveiros de Castro” Common Knowledge 22: 393-414 .

Stewart, Eric C. 2012. “Reader’s Guide: New Testament Space/Spaciality.” Biblical Theology Bulletin 42: 139–50. Strieber, Whitley and Jeffrey J. Kripal. 2016. The Super Natural: A New Vision of the Unexplained. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tinker, George "Tink", "The Stones Shall Cry Out: Consciousness, Rocks and Indians," Wicazo Sa Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, Colonization/Decolonization, I (Autumn, 2004), pp. 105- 125

RSS Feed

RSS Feed