...“apprehending the world is not a matter of construction but of engagement, not of building but of dwelling, not of making a view of the world but of taking up a view in it” (Ingold 1996, 121; Poirier 2004, 61).

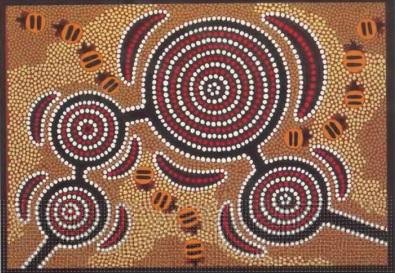

http://art-educ4kids.weebly.com/aboriginal-art-and-patterning.html

http://art-educ4kids.weebly.com/aboriginal-art-and-patterning.html Our entanglement with technology has revolutionized the way social theorists reflect on human relationship to things.

One of the best full investigations of this is via archeology, a field devoted to interpreting things.

In Defense of Things: Archaeology and the Ontology of Objects by Bjørnar Olsen painstakingly theorizes how through mass culture and manufacturing, critical theorists called for a rejection of things and now have reconciled human relationships to things by de-centering the human.

This central argument is a material-semiotic relationship among humans and non humans in which what is real is reliant on its relationship, an actor network in which all elements of the network are actors - or rather actants to replace the assumption that humans were the only agents of any event. Latour argues that action is ‘not a property of humans but of an association of actants’ (Latour, 1999: 182; emphasis in original).

As Latour, Cellon and Law describe what has been called Actor Network Theory (ANT), relationships as a central feature of a cosmological upturn - humans, animals, objects assembled to create an event or action. Latour should be credited with turning objects as ‘matters-of-fact’ into uncertain and disputed ‘matters-of-concern’ (Latour, 1996a; 2000; 2002)

Folding

Bringing a thing to life

So, then, who or what - brings a thing to life?

Anthropologists have long encountered indigenous community's theories of being, but recently there has been a stronger trend to take these ontologies as a challenge to the substantive Western notion of being.

What methodologies help us encounter worlds unlike ours in their relationship to the unseen? These Others are usually aboriginal, or poor and "superstitious" or variously "non-rational." They are historically an irresistible target for economic integration, educational assistance and civilizational uplift.

Deborah Rose Bird's reflexive epistemology allows her to be open to Other intersubjectivities. Rose Bird is one of a number of ecologically reflective ethnographers who have studied aboriginal communities in Canada and Australia. Goulet and Miller as editors of Extraordinary Anthropology: Transformations in the Field propose that anthropologists move out of their "taken-for-granted body of knowledge (academically and worldy) and truly enter the realm of the Other's lifeworld." Bird Rose's article is among the contributors in this volume who refer to "extraordinary" experiences that shook their original skepticism. These occurred as religious conversions, in visions, often in dreams. Goulet and Miller are not concerned with "becoming native," a charge intended to discipline anthropologists who have lost perspective of their project and are no longer "objective." More often than not, the anthropologist's "extraordinary" experiences in the field do not appear in their monographs. In this sense, this collection and Goulet's earlier Being Changed by Cross-Cultural Encounters (1994) refuse to "reverse the charge" as we used to say in the old days when there were collect calls. (For millennials this means a phone call that you bill to the people you are calling.) They take responsibility for their engagement - often unbidden- in someone else's world. Bird Rose's reflection on recursive methodology is one of many (often referring to Fabian's Out of our Minds) who are changed by encounter.

Deborah Bird Rose's work among Australian Aborigines promotes an ethical ecological anthropology. She argues that an epistemological transformation was a necessary aspect of her learning process as an ethnographer. But one must "learn how to learn." For this, she cites Bateson's call for "detero-learning," a reflexive process of participant observation that requires one's whole being. "This openness leads to an anthropology that is dialogical, reflexive, and attentive to process, and that ex- tends beyond the human and into the lives of plants, animals, and all manner of extraordinary beings and modes of communication." (89)

For Bird Rose, a recursive epistemology is a "situated connectivity," a process of knowledge production that occurs when both knower and known are mutually embedded in an encounter and knowledge is exchanged and changes both parties. She defines it via Bateson as

...events continually enter into, become entangled with, and then re-enter the universe they describe” (Harries-Jones 1995, 3). Recursions are iterations and entanglements; they are “rampant” in ecological systems (Harries-Jones 1995, 183) within which human societies are embedded. ...The anthropologist’s thought is shaped by her teachers as her life shifts more deeply into relationships with people, places, and concepts that become increasingly constitutive of her own thought and being. While fostering porous proximities, a recursive epistemology does not lead toward homogeneity. Rather, it works productively with difference, change, and exchange. (91-92)

This photo is clever trick on the nature of recursion, but it does not express the rich connectedness that Rose Bird via Bateson describes. Recursion in this case is an important feature of computer programming. (You notice that the regress will continue unless you direct it to STOP.) But in Bateson's cybernetics, recursion is not so geometrical.1 It is "entangled" and the knowledge one gains informs the knowledge one gleans. This requires an openness to mystery, and a responsibility to what we learn.

Rose Bird situates this in Northern Territory of Australia and "friend and teacher Jessie Wirrpa." Already, then, the "informant" is the teacher. Jessie's world included the dead, the living, and other creatures. On a walkabout, Jessie "called out" to her ancestors,

“Give us fish,” she would call out, “the kids are hungry.”.... When the cockatoos squawked and flew away, Jessie laughed because they were making a fuss about nothing. When the march flies bit us, we knew the crocs were laying their eggs, and Jessie began to think about taking walks to those places....The world was always communicating, and Jessie was a skilled listener and observer. (91)

Bird Rose speaks to root principles that involve an acceptance of a world of patterns, filled with both human and non-human sentience based on an "ethic of intersubjective attention in a sentient world where life happens because living things take notice." This "taking notice" is the most important part of her work as a participant observer who is learning to learn. And ask Bird Rose "takes notice," the questions, perceptions, hypothesis she came with transform. (92)

In time, Jessie dies, and Bird Rose tries to act on the practices she has learned. She wants to visit a river to honor Jessie, but the first times she goes, she does not "call out". Only later, when she visits a river that she and Jessie visited together, can she "call out" with clarity. When she reflects on this, she believes it is because the "world at that time was not just a place, it was a presence. I could hear awareness, and so I could call out." (94)

But this profound moment, ironically made her feel voiceless in the academy.

These boundaries, these limits to what is sayable, are made evident primarily by being breached, and that rarely happens, so usually it may not be apparent that in an academic context that is founded in seminars, lectures, letters, articles, books, and coffee breaks, there are actually some terrible silences.

For Rose Bird, recursive epistemology has transformed her way of noticing and being. Normative anthropology's reductionist approach to other worlds is now a double death. She continues to argue from here to the ways this double death leads to the devaluation of the environment. This process then, is not only epistemological. It is an ethical response to the other, and a method that changes one's positionally altogether. What began as a doctoral study becomes an call for engagement. The hidden anthropologist's hand is now visible and sometimes it is not clear who is writing whom, Jessie or Deborah. But this work on epistemology - on knowing - has shifted of late to ontology, being. And we shall take the figures Rose Bird invokes at the start of her article when we consider relational ontology.

Endnote

1. Norbert Weiner defines cybernetics as the control and communication in the animal and machine; it is a study of how systems function through feedback and control.

Cited

Bird Rose, Deborah. Recursive Epistemologies and an Ethics of Attention, In Extraordinary Anthropology. Transformations in the Field, Eds Jean-Guy Goutlet and Bruce Granville Miller, University of Nebraska Press, 2007, 88-102

Bird-David, Urit

Harries-Jones, P. A recursive vision: Ecological understanding and Gregory Bateson. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1995

Poirer, Sylvie, Reflections on Indigenous Cosmopolitics - Poetics, Anthropologica, Vol 50, No. 1, L'experience et la problematique de la (de)colonisation: Autour de l'oeuvre d'Eric Schwimmer. (De)colonization as Experience and Field of Enquiry: The Work of Eric Schwimmer (2008), pp 75-85

Schwimmer, Eric, John Clammer, Sylvie Poirer, Figured Worlds, Ontological Obstacles in Intercultural Relations 2004, Tim Ingold 2000: 149

Wiener, Norbert, Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Paris, Hermann et Cie - MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1948

RSS Feed

RSS Feed