Cambodia, 2003

I wrote this after an evaluation trip to Khmer Rouge "reintegration areas" in western Cambodia. I consider the idea of witness and narrative.

For more than a decade, I'd been a tutor in Minneapolis, staff at the Philippine Refugee Processing Center, worked with at-risk Cambodian boys and girls in projects of West Oakland, or a researcher in the bright new offices of hyphenated Cambodians—American, French, Australian, Swiss, who had returned to Phnom Penh to participate in its transition to democracy.

For them, I was an ambivalent figure, a compatriot of sorts, witness to their discursive feat defending hybrid citizenship as a necessary aspect of new Khmer nationalism. (Within the Cambodian domain of peacemaking, local Cambodians treated foreigners with more equanimity than former refugees who had to negotiate twice for authenticity—with both homeland and naturalized countries.)

********

It might have been our close call with ex-Rogue soldiers that inspired Kennaro to talk.

He was translator for interviews with former Khmer Rouge soldiers and their experience in new “integration zones” since the massive KR defection in 1998. We'd bounced along deeply rutted roads from Battambang to the infamous Sampot, the Khmer Rouge stronghold in far western Cambodia.

Sampot was desolate, wide swathes of parched plots devastated by rampant logging, and cut off from the world. When we got to the ramshackle town, it took some time to rustle up the "focus group" of toughened Khmer men and women to talk about their plans for integrating into a contentious Khmer "democracy". I cast a glance at the dingy cots and decided we would drive back to Battambang that night. Kennaro agreed. But he knew better than me what came in the dark.

Slowy, painfully, the van heaved over potholes along the former KR highway. It was as black as the belly of a whale.

The headlight five men wildly waving. Then I saw the rifles, then in one sickened moment, I realized what it meant. Kennaro had already gripped the driver’s shoulder, speaking urgently in Khmer. The driver pumped down on the old car. It tumbled foward. They called out, garbled drunk and angry. But they didn't shoot. And they waved us past.

We sat in a blank silence. Then Kennaro began to talk. He was a Khmer Rouge soldier, he'd chosen to survive. At the end, when the Vietnamese arrived, he fled with two buddies to the Thai border. It was a moonless rainy night. "We walked on to a muddy minefield," Kennaro's voice dangled in the dark. Tripping over mangled bodies, they realized too late. There was one explosion. The two waited, called out, waited. Then, inching forward, one step, next. Kennaro heard a second blast. His second friend, weak with shock, cried that his legs were gone. "I crawled across the border." He landed in the hands of casually cruel Thai border police who conscripted him as their servant.

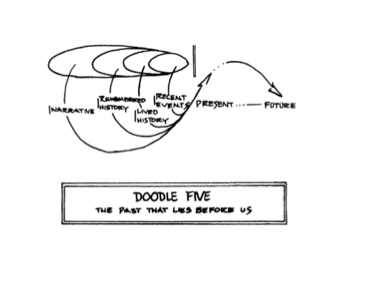

There were a thousand thousand stories. In the Philippine camp, we'd collected them from families enroute to America. Each story its own horror.

But this story was a painful particular gift, this testamony in the dark. I remember this story as I stared at the headlight tunnel before us. Maybe Kennaro told it because of the afternoon among Khmer Rouge, maybe the near escape from a KR bandit’s “jackpot”– a foreign woman with no body guard in a car on a dark passage in the poorest and least patrolled part of Cambodia.

What we escape and how we retell it. What it means to witness.

This is a reflection on those who tell the story. But not those who are chosen to receive it.

Sisterhood after Terrorism

I wanted to know about "sisterhood after terrorism."

Here, I was subject to my own interviews, a Taglish-speaking “Manila girl,” my first seventeen years raised there (see Manila Days, blog memoir) with "fraternal workers" on church and social justice. I was also white, an American, aligned with one or more divides of the left. Here, my parents, my credentials, and who had “spoken for me” barred or opened access.

While in Cambodia interviewing Cambodian Americans, I was an authoritative citizen. In the Philippines, I was, as I sometimes ruefully put it, “target practice.” I was standing in for the enemy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed