What do we mean by Chiasm?

As an organ of sight:

1. The optic chiasm or optic chiasma is an X-shaped space just in front of the pituitary gland where optic nerve fibers pass through to the brain. Fibers from the nasal half of the left eye and the temporal half of the right eye form the right optic tract; and the fibers from the nasal half of the right eye and the temporal half of the left form the left optic tract.

As a literary device:

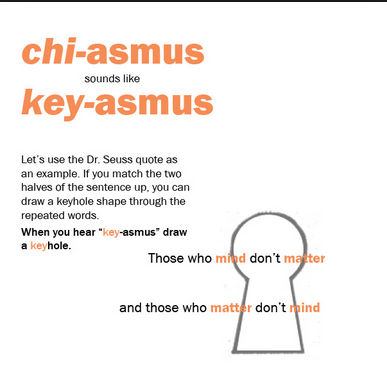

2. A chiasm (or chiasmus if you rather) is a writing style that uses a unique repetition pattern for clarification and/or emphasis: Two parallel clauses, in which the order of elements in the second clause inverts the order of the first.

3. As Merleau-Ponty's notion of the body as flesh, the intertwining of touch and vision, in The Intertwining—The Chiasm (find Here) crossing over of both objective and subjective experience. You must read and read again to understand what M-P is trying to do in his posthumous The Visible and the Invisible, a dense phenomenology of sensibility. Given my interest in the invisible, I first wanted to understand Merleau-Ponty's characterization of this "intertwining" in phenomenology. But I was lost in the chiasm, and turned to feminists to help me out.

So, what is feminist phenomenology? (Think Butler, Marion Young, Grosz, Irigaray) Merleau-Ponty counters Descarte's split body/ consciousness with an affirmation of the interconnectedness of body-mind. If this sounds so corporeal, is there a feminist cautionary? Elizabeth Grosz notes that feminists find in Merleau-Ponty first an ally and then a disappointment in his avoidance of sexual difference and specificity. Only Irigaray takes on the Chiasm, his last work on The Visible and the Invisible which turns to the flesh and its reversability. Cecilia Sjöholm's reading-of-Irigaray-reading-Merleau-Ponty on the "chiasm" is a way to think through human perception, which is, after all, M-P's project. 1

For M-P, we are sensible to the world through touch and vision, an interactive process of reversals. The most familiar example of M-P is the hand that touches its other hand. One hand as subject touches; the other as object experiences the touch. Though both are part of the same body, they do not merge. They are mutually constituted. And so it is with the look, he argues. The look "envelops, palpates, espouses visible things: So sight has the same ambiguous nature as touch, and it is from its own 'objective' side that the objectivity of the visible world is generated.” These reversals constitute the flesh which Sjöholm describes as "an excess produced in the intertwining, introducing otherness in relation to the corporeal subject's selfsameness." One sees and is seen but cannot see how this occurs. One cannot see oneself seeing, is only be aware of this though the way things become visible; they in some manner look back at me. This is a kind of narcissism of the flesh, says M-P,

Once again, the flesh we are speaking of is not matter. It is the coiling over of the visible upon the seeing body, of the tangible upon the touching body, which is attested in particular when the body sees itself, touches itself seeing and touching the things, such that, simultaneously as tangible it descends among them, as touching it dominates them all and draws this relationship and even this double relationship from itself, by dehiscence or fission of its own mass. (Merleau-Ponty 1968, 146)

French feminist Irigaray's argument, even when charted by Sjoholm, is difficult to track. But ultimately she argues that M-P's self-sustaining body represses the presence of bodies it chooses not to see. It creates the invisible. Irigaray challenges the notion that subject and object can hold reversible positions. Sjöholm reminds us, "the subject engulfs or envelops, receives or rejects, caresses or eats the object, but never replaces it."

Irigaray argues that Merleau-Ponty's metaphors, though sexual, do not refer to a sexualized ontology. Thus the sexualized relationship hides sex and since the male (through the vision, the gaze) is dominant, the female (through the tactile). Thus M-P's flesh has implicitly endowed with attributes of the female, and M-P does not claim any debt to maternity. (Grosz 1994) Merleau-Ponty's concern about the invisibility of the flesh sends him into increasing regressions that end in the womb. Sjohom argues what we suspect already: this regressive chiasm is linked to the exclusion of the female body, which cannot foreclose sexual difference. "What Merleau-Ponty's chiasm lacks is a distinct, symbolic division between self and other. 2 Irigaray problematizes the alterity that one makes visible.

1. Cecilia Sjöholm "Crossing Lovers: Luce Irigaray's Elemental Passions” Hypatia 15.3 (2000) 92-112

Evans, F., & Lawlor, L, Eds, Chiasms. Merleau-Ponty's notion of flesh. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2000

Grosz, Elizabeth, “Lived Bodies: Phenomenology and the Flesh" in Volatile Bodies. Towards a Corporeal Feminism, Indiana University Press, 1994

Merleau-Ponty, M The Visible and the Invisible, Basic Writings, ed. Thomas Baldwin, Routledge, 2004.

130-55

Olkowski, Dorothea, and Gail Weiss, Eds. Feminist Interpretations of Merleau-Ponty, Penn State Press, 2010

As an organ of sight:

1. The optic chiasm or optic chiasma is an X-shaped space just in front of the pituitary gland where optic nerve fibers pass through to the brain. Fibers from the nasal half of the left eye and the temporal half of the right eye form the right optic tract; and the fibers from the nasal half of the right eye and the temporal half of the left form the left optic tract.

As a literary device:

2. A chiasm (or chiasmus if you rather) is a writing style that uses a unique repetition pattern for clarification and/or emphasis: Two parallel clauses, in which the order of elements in the second clause inverts the order of the first.

3. As Merleau-Ponty's notion of the body as flesh, the intertwining of touch and vision, in The Intertwining—The Chiasm (find Here) crossing over of both objective and subjective experience. You must read and read again to understand what M-P is trying to do in his posthumous The Visible and the Invisible, a dense phenomenology of sensibility. Given my interest in the invisible, I first wanted to understand Merleau-Ponty's characterization of this "intertwining" in phenomenology. But I was lost in the chiasm, and turned to feminists to help me out.

So, what is feminist phenomenology? (Think Butler, Marion Young, Grosz, Irigaray) Merleau-Ponty counters Descarte's split body/ consciousness with an affirmation of the interconnectedness of body-mind. If this sounds so corporeal, is there a feminist cautionary? Elizabeth Grosz notes that feminists find in Merleau-Ponty first an ally and then a disappointment in his avoidance of sexual difference and specificity. Only Irigaray takes on the Chiasm, his last work on The Visible and the Invisible which turns to the flesh and its reversability. Cecilia Sjöholm's reading-of-Irigaray-reading-Merleau-Ponty on the "chiasm" is a way to think through human perception, which is, after all, M-P's project. 1

For M-P, we are sensible to the world through touch and vision, an interactive process of reversals. The most familiar example of M-P is the hand that touches its other hand. One hand as subject touches; the other as object experiences the touch. Though both are part of the same body, they do not merge. They are mutually constituted. And so it is with the look, he argues. The look "envelops, palpates, espouses visible things: So sight has the same ambiguous nature as touch, and it is from its own 'objective' side that the objectivity of the visible world is generated.” These reversals constitute the flesh which Sjöholm describes as "an excess produced in the intertwining, introducing otherness in relation to the corporeal subject's selfsameness." One sees and is seen but cannot see how this occurs. One cannot see oneself seeing, is only be aware of this though the way things become visible; they in some manner look back at me. This is a kind of narcissism of the flesh, says M-P,

Once again, the flesh we are speaking of is not matter. It is the coiling over of the visible upon the seeing body, of the tangible upon the touching body, which is attested in particular when the body sees itself, touches itself seeing and touching the things, such that, simultaneously as tangible it descends among them, as touching it dominates them all and draws this relationship and even this double relationship from itself, by dehiscence or fission of its own mass. (Merleau-Ponty 1968, 146)

French feminist Irigaray's argument, even when charted by Sjoholm, is difficult to track. But ultimately she argues that M-P's self-sustaining body represses the presence of bodies it chooses not to see. It creates the invisible. Irigaray challenges the notion that subject and object can hold reversible positions. Sjöholm reminds us, "the subject engulfs or envelops, receives or rejects, caresses or eats the object, but never replaces it."

Irigaray argues that Merleau-Ponty's metaphors, though sexual, do not refer to a sexualized ontology. Thus the sexualized relationship hides sex and since the male (through the vision, the gaze) is dominant, the female (through the tactile). Thus M-P's flesh has implicitly endowed with attributes of the female, and M-P does not claim any debt to maternity. (Grosz 1994) Merleau-Ponty's concern about the invisibility of the flesh sends him into increasing regressions that end in the womb. Sjohom argues what we suspect already: this regressive chiasm is linked to the exclusion of the female body, which cannot foreclose sexual difference. "What Merleau-Ponty's chiasm lacks is a distinct, symbolic division between self and other. 2 Irigaray problematizes the alterity that one makes visible.

1. Cecilia Sjöholm "Crossing Lovers: Luce Irigaray's Elemental Passions” Hypatia 15.3 (2000) 92-112

Evans, F., & Lawlor, L, Eds, Chiasms. Merleau-Ponty's notion of flesh. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2000

Grosz, Elizabeth, “Lived Bodies: Phenomenology and the Flesh" in Volatile Bodies. Towards a Corporeal Feminism, Indiana University Press, 1994

Merleau-Ponty, M The Visible and the Invisible, Basic Writings, ed. Thomas Baldwin, Routledge, 2004.

130-55

Olkowski, Dorothea, and Gail Weiss, Eds. Feminist Interpretations of Merleau-Ponty, Penn State Press, 2010

RSS Feed

RSS Feed