But this, this, was needful now. I've come to do my own work, to disentangle my evangelical-charismatic-pentecostal Oregon-Chicago-Minnesota conjunction of the last 6 years. To "stand up" in a theology, no more crouching to fit in. To braid the strands of my life so far. So while Union liberated -- engulfing us in the politics of queer caucus, social justice, and Black, queer, feminist, third world. liberation theologies -- it was also allergic to the "spiritual" not to mention white girls speaking in tongues (Tagalog, no problem, it was that angelic kind).

Well. One liberates while it isolates its version of the unpalatable.

Nonetheless, those Seminary years are an exhilarating chance to weave my "three revolutions" together. A year later, this paper, Convergence, written for Bev Harrison's Feminist Theology course in Spring 1988 is the basis of an MDiv thesis on exile and my memoir blog Manila Days...

So let's begin with the poem that frames Manila Days...

We hunch, my sister and I,

in the paunch of our acacia tree

(we are playing hide and seek)

but army ants are crawling over her and me.

She tugs at her red cotton dress.

She pulls at her panties,

"I want to swing on the tarzan vine."

"No you can't, they will see,"

but she grabs it, swings,

scampers back up the tree.

Laling runs out, scolding,

"Johanna come down!"

"ayaw ko!"

"halaka, your nanay said no! "

"Johanna go down before Laling gets mad."

"you come too."

"sige na, I'll go with you."

Kerry, 1969

The warp of my story is joy "filling up and spilling over." Joy to know "my soul is rested." Joy that does not neglect anger or suffering, but takes them in. Joy that is the strongest passion for justice, which is a serious business, but also deserves its humor. And though joy might be someone else's strength, it isn't mine til much later on this journey.

The woof is the tension between revolution/destiny as I have come to understand them. A revolution overturns the old order. After a revolution, a society must rewrite its history, it must, that is to say, recreate its identity." says H. McCabe My life has had three current revolutions: 1972, 1976, 1981. Each revolution forced me into a new relation to the world and alienated me from the earlier community. But how do we reconstruct identity; are there constructive ways to leave old paradigms and move into new ones? What criteria do we use to determine what to keep and what to change? What happens when the revolution is about the criteria itself? These have been perennial problems to me, and this essay provides the raw material for the questions, it doesn't intend to answer them.

My sense of destiny keeps me moving into the morning ("whither thou goest..."). I believe that there is a certain "meantness" to life. Destiny is not as much pre-ordained action, as a deeper order that might not be discerned at first glance. It is a mystery that calls us into relation to it; it calls us into the revolution, and out of it. My great dread is to lose a sense of that inner call.

Though destiny can call us into uncharted waters, my sense of destiny is closely bound to my deep respect for the "old ways". If a revolution says that the old gods are an empty cistern, and destiny says: dig deeper. I stay and dig, believing I will find springs in the old well. I am fascinated with shamanism, Native American spirituality, and the "deep structure" of ritual.

This culture is so fragmented and unrooted that its spirituality and commitment sometimes feel like thin topsoil. A Filipino friend said to me once, "you Americans are so 'ningas kogon. You're like a grass fire that burns everything up so fast. You don't know how to wait, or how to bend like the bamboo. You always have to change things, even if they're already working. And you think the new way is always better."

And so I stand, between the old ways of fatalism and the new ways of self-determinism. I choose to focus primarily on the second revolution - my religious conversion experience - not because it is the most conventional answer to a "spiritual journey" question, but because I see it as the crux of revolution and destiny. In the intervening years, it has been the most difficult part to reconstruct.

Chicago, 1972-73

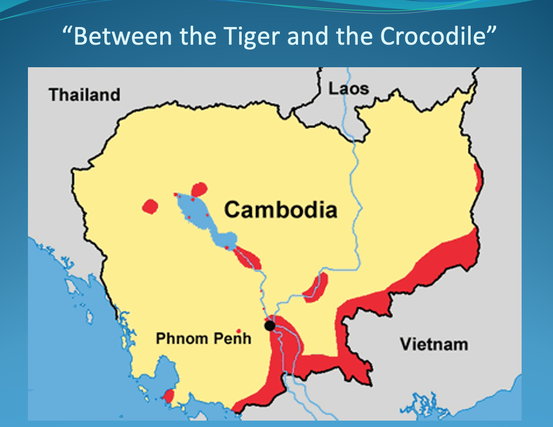

After seventeen years in the Philippines, I was joining my family who had gone ahead to Chicago the year before. I was with family friends when the violent typhoon ravanged Luzon and Martial Law violated democracy in the Philippines. My first revolution had two faces: first, the drastic change in the Philippine power base overnight. It destroyed any sense I'd kept that one could trust the media, goverment in power, and that private life was safe.

The second was a struggle with my identity as an American. I was back from exile, but uncomfortable with these foreign gods. White on the outside, I was a strange amalgam inside of "Manila girl" and missionary kid. In many ways more sophisticated than my peers, I was dreadfully afraid of Americans: their sexual habits, their brazen behavior, their ability to argue. In their strange confidence, they presumed that they were right. To me the arbitary world was so full of relativity. Only politics in the "old world" was uncompromising.

So, when I told my story through my poetry, it was a deep fracture between the old world and the new. I defined myself as a misfit, a missionary kid who, like the Vietnam vets, represented an ignoble experience that Americans did not want to hear about. My own pain had no place because it didn't have a category.

By this time last year,

sampaguitas were crazy with bloom.

Now, the sharpen-scissor man pedals on

the lawn and I don't come.

The itchy worms plumb empty lines.

And the heat begins to whisper

through the dying kogon grass: halika,

kailangan kita, bumalik na, mahal.

1972 (17)

Triste Tropiques

midnight white

with lizard moult,

the vagabond cicadas hum.

then come the rat-dank ranks

they scuttle on soft paws

like sabotage around

around the ledge

above my bed. The same sound

drags its crooked claws on glass

as frozen branches

shudder. Ay!

I heave from tropique

heat to queasy snow

in this strange, uneasy gloom,

and cancerous, the white sky

blooms.

1974 (19)

My next revolution began at the University of Chicago in consciousness research. Since the political world could not be trusted, all cultures relative, and my own intelligence so much more experiential than my peers, I found real consolation in an area I knew best - the psychic world. I participated in the Sleep Lab, dream research, tried LSD, and became a kind of hybrid "subject" for Erika Fromm's work with hypnotherapy. I was "Billy Pilgrim" traveling to spaces where the old God was cast out.

Crack the panic-draining hourglass,

Spill the crystals, only sand.

Shatter angry condescending idols.

Gold-leaf halos flake to tin

and you are not a slave

to their command...

1974 (song)

But God happened to me anyway, during the month-long hypnosis research project of Erika Fromm. We were supposed to hypnotize ourselves daily for an hour, and keep a journal of our experiences. I'd find a quiet spot and descend by visualizing a descent in water, counting downwards. When I felt I'd "landed", I'd request a "state" from my subconsciousness. A number would register, which I understood to be my depth. I usually registered at around 40.

I was a tomato, an eagle, I regressed to five. I travelled to wild, imaginary places, one where I met grey-furred creatures with wings and no faces.

Sometime during the second week, I "went down" to 70, the deepest I had ever gone. Because I was so deep, I tried to hallucinate, and when it didn't work, I returned to my chair and waited.

I heard, "Kerry."

"What do you want, Lord," I responded.

And suddenly, as a flash of light broke, I began to weep.

"Let me in," the voice said.

"I can't let you in, you know that," I said, "but you can choose to come in on your own." "

Let me in" it said again. By now, I was truly sobbing,

"You know I can't let you in, "I said "but you can come in." I

t didn't try. It left me. And I "woke up" wailing for my mother in my childhood bedroom.

When that subsided, I went down some stairs (still in another world) and entered the home of an old woman named Shanti.

She talked about life , death, and the stars, as we stood by her window in the underworld. I don't remember what she said.

I returned to waking life truly shaken. Had I gone so far "down" I'd unearthed my old religious fervor without any resistance, and it wanted to come back? Or, was that really a Voice outside of me, my ego-skin so fragile that I could finally hear God, that old God I had been trying to escape. Or maybe it wasn't old material rising up in me, but something- someone-whole Other.

I was afraid to go too far down after that. Instead, I went into a deep depression.

blackbellied the beast

turns and trembles

between frozen ground.

and I am tired of mad dreams

and I am weary of this enduring vagueness.

The river, the water,

the encumbering earth,

the dark air of posthumous glory

every bridge belongs, at end,

to Berryman.

1975 (20)

*****

Months passed, and my depression and dreams grew worse. It was as though some pandora's box had unlatched. I woke up one night with a disturbing sense that I was being assessed by other presences. I was frozen with fear. Finally, the presences left, not my own growing realization that I was attracting craziness because I couldn't take in wholeness.

I decided to drop out of school and travel until I could resolve it. A series of powerful dreams punctuated my journey out to Oregon. The first occurred on a camping trip in Colorado. We had picked a site that I knew had something evil about it. Like witchcraft, I thought. That night, from our site, we watched a dry lightning storm.

I am lost in a lime forest of white and green-lined skeletons of trees. Even the forest floor is white lime. It's a place of death. Two people are trapped here - a witch and me. We know that only one of us can escape. As I realized this, witch holds a knife above us, as we wrestle, she plunges it into my chest. I can feel it. I die. And rise out of my body. I stand beside it. That feeling, that grim feeling, is the same feeling I have when I take the knitting by the fire. Because when I turn, I see the witch disheveled, her head in her hands. And I know - the only way out of the forest is to die by another's hands. She know now too, that she's condemned to the forest forever. So I pick up my body to leave the forest. After a while, the body's too too heavy, and I let it drop, and keep walking.

I awoke from that dream with a solemn sense of resolution, but I didn't really know what the dream meant.

In the following weeks, I hitch hike to Oregon, visiting a "woodswoman" friend outside of Eugene who suggested I visit someone up in Portland and at Mount Hood. Without much else to do, I hitched up there. In Portland, on the second day, I had a vision.

I'm lost in a forest, but this time, it's full of life. I can communicate with the trees and the animals by telepathy. I understand how the forest is alive, what the birds mean when they sang, what the trees are saying when they "swish". I understand that the forest has an ancient code, not "good" or "evil" but just in an indifferent way. I ask for permission to use its power to shatter a stone. Just to test it, and my request is approved for this trial only. I focus on a rock, and it explodes, fragments flying through the air.

Then, colors change, and I'm trapped in a net - caught by people from University of Chicago who think I"m a wild child. I am "returned" to U of C, the light is was red and murky. I feel such deep despair. I still have power in my hands so I try to communicate with it. I put my hand on my friend Carol's chest. It exploded into light, and she's changed. Then I go to Larry' Goldbaum's brilliant Physics professor and say "your language is so crude. Is English all you can speak?" I put my hand on him, and the same thing happens. Tears rolled down his face.

Last scene, the power and ability to hear in the other language is fading. My consciousness is murky.

Last thought as I wake: "how will I ever get back to the forest; I will be worse here than I was before."

My body is whizzing when I come out of the dream-vision, and I say "I have to clear my channels." I think the answer is Mount Hood and to stay there for a few days. I have to do this, no matter what it took. I needed to get out of the city and settle somewhere. I felt lost, filthy spiritually, and deeply depressed.

So I hitched up to the top of Mount Hood, and found a way back down halfway to the store I'd been told where to meet people. But it was closed on Tuesdays. I heard voices around back, and found two men reading the bible. I went up to one of them, the one with the scraggly blond beard, and said, "do either of you know Joe Farrel." He looked up at me and said , "I'm Joe". He took me to lunch at the Cooke Ranch.

I knew a man was holy once

and now is only Christian

he said, "you can stay and hear the word,

or you can eat and run. It rains here

all winter, and the winter's just begun.

Chorus:

It comes to this:

when you got no place you can call your own,

you gotta find it in your soul

well, I've run the land like a contraband,

trying to escape the cold inside me.

I said "yes, lunch would be fine,"

began to eat before they prayed.

And Mother Cooke read from The Book

in a Hallelujah Voice.

They praised the Lord like aspirin

till I felt a little more like rejoicing.

1976 Song (20)

It can only be said that I fell in love with God, with Jesus. I was swept away by such joy during worship that I danced and sang until I was full of light. The purity of my desire matched the single-mindedness of my direction. I wanted to be aflame with the spirit, to give my life over to that loveliness. And because the lifestyle was an anathema to my earlier political and intellectual instincts, I embraced the Cooke Ranch dogma as a form of self-humiliation.

Oregon was the culmination of my deepest revolution. I retold my history from a classical conversion perspective. I rediscovered hope and a future, something to live - and die - for. I found a blushing intimacy that was also bold and empowering. This Christianity was "magic"; it too knew spirits and visions.

I remembered the dream, and I was afraid that if I went back to Chicago too soon, I would be worse than when I left. So I tried hard to make the revolution take control, to change my intellectual framework. I burned up my journals, I cut myself off from my past. I thought: I will do this like spiritual surgery, I will just stop my critical thinking to make this 'take.'

So when I returned to Chicago and to U of C to "face my dragons", I had become a stranger (the word was out that I'd "gone off the deep end"). The consciousness work ended. But in those two years, from 1977 -79, I reconstructed a religious identity and found a new community. To adjust Oregon religiosity, I joined a Catholic Charismatic prayer group and another prayer circle composed of black Chicago women. I sat at Friends meetings. My criteria was simple at first - is it polluting, will it give me too much freedom? But later, I returned to an old criteria: does it feel authentic? A different tentative version of that revolutionary spirit returned with seminarians at McCormick Seminary, who were connected to my father's work.

Should I go to seminary? It was too soon to have this fledging faith challenged. At the invitation of family friends, I moved to Minnesota to work in refugee resettlement. It was important to find somewhere "safe", a like-minded group that would support my religiosity. My impulse to sample and assimilate such various experiences might distract me from my Christian destiny. So I moved into a Christian community, a "house church" composed of post-college white, middle-class evangelicals in most of whom had conversion experiences in college. But I had been to the moon and they were dabbling in its phases.

So I started a women's task force to look at the issue of women and ministry since the group was still too conservative. So slowly, I returned to a more familiar progressive politics, but it was slow, and I stayed until it was too painful to bear.

In 1981, The third revolution, which had been rumbling for some time, erupted. I fell in love with a woman.

There is iron in our blood.

Enough for the letting and labor,

less left for matyrdom.

Then, past pretending,

let us speak of elemental urges -

what roots the mandrake,

who breaks the soil.

1981 (26)

"Imagine my surprise," sings Holly Near. And yet, it was no surprise. It was a royal flush; it was like flushing qrouse out of the tall grass unawares, and gasping mid-step as they take to the air. I sorted through my past again, piecing clues, and quilting together a story of my lesbian sexuality (I couldn't say the word for a couple of years). I talked with my parents, sisters, and select friends, who were supportive and helpful. I was frightened, exuberant, head over heels in love. We were in many ways opposites, and we were collegues. I revelled in the ability to learn without condescension and collaborate without competition.

But it was a relationship of triangles - she was an atheist in a long-term relationship with a man, I was in a life-long relationship with God. I felt being with her meant that I had forfeited my destiny. It was a spiritual tourniquet. I prayed for an answer, release, but nothing came. Then, spiritual exile, a split and hidden life for one and a half years.

I was again outsider, this time in a comfortable community that treasured faithfulness, family and piety. After coming out to the church elders, a number of tearful meetings ensued. They really didn't know what to do with me, and since I wouldn't repent, they thought (and so did I) that it would be better for me to leave.

In our last meeting together, one of the elders had a vision. He said, We are sitting with our backs turned towards a great fire. Every once in a while, someone will furtively glance across the fire and lock eyes with someone else, and a charge of life will run through them. Only Kathryn is standing, facing the fire. But her eyes are closed.

The vision haunted me. I longed for a community that had no sexual rules, no god. Jenise and my relationship lasted five crazy years. After we had broken up, I went back to visit the cabin where we'd spent so much time together. As I walked down the dirt road, I was struck by a keen, clear silence - no lamentation, no anguished prayers, no raging jealousy to expel. I'd faced that fire.

It took coming to Union to begin to refine the fire, and to sort through my own revolutions, to find a place where they converged.

In the intervening years, I worked in a refugee camp in the Philippines, nestled in the mountains by the South China Sea. It brought home the first revolution, and in fact, I was present for the "people's power" revolution in 1986! It set me on the path to reconcile with the second revolution: I applied to Union Seminary on February 7th, election day. And it brought the third revolution to its climax. I realized that whatever work I was to do in life, it had to be with women.

Poles through horses,

straw through poles,

Dorothy, being Dorothy,

was late to the shelter and

found Oz. And by her sheer

honesty, made strange

companions friends, broke

the witches' spell, won herself

a following, but being

Dorothy, longed mostly

for the Kansan busom of Aunt Em.

1984

***

I gave my grandmother yarn once, fushia, royal blue, magenta, egg-yellow, lots of colors. I said, grandmother, please knit me something that doesn't have symmetry, just let the spirit move you. She looked at me startled, she who knit by pattern and plan. I'll try, she said a little half-heartedly. Well, the shawl that came back to me was exquisite, it was wild, cultivated canopy of color. She laughed delightedly as she described it. A statement on her life as much as mine.

The story is a weaving, but not Penelopes' skein, woven in the daytime, unraveled at night. At thirty-two, I can see some themes shaped in the warp and woof. I don't know what the full pattern will be, but it progresses, it progresses. It's a beautiful piece, and better laid on the floor for story telling by the fire or wrapped around somebody's shoulders, than curled up in the attic or hung on the wall. And I need all its colors, and I treasure its textures. The knotted sorrow and struggle, the silken pleasure. And I love the woman who throws the shuttle, who shifts the pedals with her bare feet, who laughs with her fellow weavers as our cloth grows.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed